This is the second part in a two-part series on China’s new generic ban on the chemical class of nitazene analogues. The first part covers the two previous times China has introduced generic bans in their attempt to crack down on the novel psychoactive substances market, analysing their effects and evaluating their efficacy. This second part will explore what we can expect of the recently implemented nitazenes ban and how it may play out in the coming years.

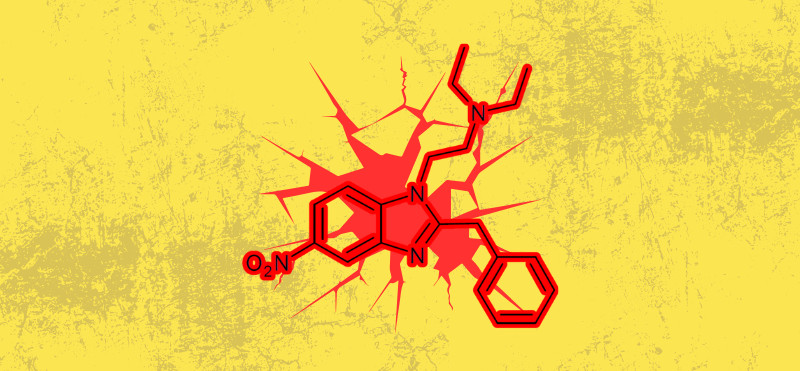

China didn’t just go straight for the generic nitazenes ban; similarly to fentanyl, it first identified and scheduled specific prominent substances. In the lead up to this year’s ban, a total of seven nitazenes had been scheduled between 2013 and 2024.

The third generic ban: a rerun of history?

Learning from past drug control efforts may give some clarity into what the future holds for Chinese-originating nitazenes. What has led to China’s nitazenes ban seems very similar to fentanyl. Timing-wise, the nitazenes ban comes amidst an ongoing trade war between the US and China: lingering American resentment towards China’s role in fentanyl precursor production has meant that the US placed a 20% flat tariff on all Chinese imports in February this year. According to Chinese state media, several tons of fentanyl and hundreds of suspects have already been arrested for drug trafficking this year.

Jason Eligh, Senior Expert on Drugs and Drug Markets at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime (GITOC), suspects that the ban was driven by Chinese political motivations.

“[The Chinese government] wanted to be seen to be doing something to address the [synthetic opioid] crisis, and their internationally-perceived role as a source point driving that crisis.”

A pre-emptive crackdown on the nitazenes industry seems like a demonstration of good faith, acting before it further deteriorates trading relations with key global partners.

Will the Chinese nitazenes ban reduce global production?

The previous two generic bans give us a wealth of clues about how this new ban may play out, and ultimately raise doubts as to its potential efficacy. Speaking to Marthe Vandeputte, a leading researcher on the pharmacology of nitazene analogues, she believes the ban may be effective in targeting nitazenes.

“It’s a pretty comprehensive ban, covering many nitazenes in circulation, which is different from generic legislation that different countries have created, where there were some substances that fell through loopholes.“

The concern with the ban is seeing a repeat of what happened with the illegal industry’s reaction to fentanyl’s ban. Banning nitazenes may just push Chinese manufacturers towards producing and exporting its precursors instead of the final product. As Eligh told TalkingDrugs, “the actual result of scheduling [fentanyl] was to move the point of fentanyl production away from China and instead to the export marketplace.”

“It is entirely possible that the same could occur for domestic Chinese nitazene production,” he added.

Similarly to what happened with fentanyl, finished nitazene production could move to countries like India, which has only banned two nitazene analogues so far, or directly in consumer markets. There’s early indications of this happening already: a 2022 report identified nitazene production in the UK and the Netherlands, sold as far as Sierra Leone and New Zealand. In 2023, a large police drug bust in the UK found 150,000 nitazene pills and pill pressing machines, highlighting local production in consumer markets.

And similarly to what happened with synthetic cannabinoids, ban-evading nitazenes with different chemical structures could also appear. As Vandeputte told us, “there’s still some nitazenes that have been described in 1950s and 60s literature that could be potent opioid agonists that would fall outside the current ban”.

New opioids on the horizon?

Eligh agreed that while the Chinese nitazenes industry could move abroad as fentanyl did, it could also trigger yet another shift towards a new substance.

“The synthesis of nitazene compounds is more challenging than that for fentanyl and its analogues. Whether [organised criminal] groups find value in synthesising their own nitazenes versus moving instead to an alternative opioid class, such as morphines, which are less regulated by comparison, is a business decision to be made.”

Vandeputte voiced a similar concern, highlighting that new opioid families could replace nitazenes.

“The ‘core structure’ of nitazenes basically contains four large building blocks; it is not unimaginable that creative chemists may come up with new ways to modify the building blocks in a way that circumvents the current ban, while retaining at least some opioid activity.”

“We’re seeing signs of ‘orphine’ analogues which may be the next class of opioids increasing in prevalence. There’s analogues of methadone that are quite potent that could come into circulation,” she commented.

Orphine analogues have been consistently detected by the UN since 2019, with five new unknown ones found just these past two years. One prominent orphine, cychlorphine, has already been detected in at least seven countries.

As she put it, “there’s endless options to choose from.”

An effectively implemented nitazenes ban could therefore stop the circulation of a large number of its analogues. Some are likely to stay in the market: protonitazene and metonitazene have remained quite present in certain markets, similarly to carfentanil. But, just as the illegal drug market cycles through new substances to produce and sell worldwide, it’s likely that a new family of opioids may come to replace fentanyls and nitazenes. These could be just as strong, weaker, or simply different than what we already have.

Is a ban enough?

Given fentanyl and synthetic cannabinoids’ ability to resist, circumvent, and innovate past control efforts, it’s unlikely that another Chinese ban will produce different results. National strategies clearly aren’t enough; international control mechanisms have also failed to stop these drug markets from moving around.

As Eligh told TalkingDrugs, “the current international drug control system is not fit for purpose in terms of being an effective mechanism to control these substances and their harm. As a global system, we need to consider another path.”

Earlier this year, criminal law experts in China published papers on international controls on fentanyls and nitazenes, calling for a “coherent global fentanyl governance framework” to be established through drug-specific international conventions. This would essentially uniformly establish generic bans on all fentanyl (or nitazenes) production across all signatory member-states, strengthen controls on pill-pressing machines and encourage cooperation between law enforcement authorities.

This approach could be better at ensuring that drug production does not easily shift to nations with weaker laws controlling enforcement. In theory, it would mean a global approach to drug control that matches the international dynamism of synthetic drug markets. However, it would also mean that a new convention would have to be signed for each emerging family of drugs – which could be a lengthy process. This approach seems to be re-using the same legislative tools of the past that have failed to control global synthetic drug production.

The researchers also recommend that reduction services and public health campaigns need to be delivered simultaneously: consumers need to be aware of changing drug markets and have the means to keep themselves safe, whether it’s through drug consumption rooms, drug checking or more.

Unless globally coordinated action is taken, illegal drug producers and markets will do what they do best: evade and adapt. Our existing toolkit of generic bans seems like it can only dampen – but not eradicate – new substances, especially synthetic ones that can be made anywhere by anyone with enough knowledge and tools. While the generic ban was developed as a tool to avoid the cat and mouse game of banning single substances, it seems to have only evolved the game into one where entirely new drug classes are developed to evade controls. In the end, who ends up bearing the costs of these changes are the ones consuming these unknown and untested substances, who often exist within health systems that don’t have the means or the tools to keep people safe and alive.