One of the longer, if not the longest, case of a death row sentence landed on Dobby’s lap. Chong Yun Fak, a Malaysian local was arrested on 23 July 1987 for trafficking 47g of heroin into Singapore. He received a death sentence in March 1992, and had been placed in solitary confinement in death row since then.

TalkingDrugs spoke with Dobby Chew, Executive Coordinator of Anti-Death Penalty Asia Network (ADPAN), and with Chong, now a 60-year-old man who has been getting re-acquainted with freedom.

Chong’s story

In the 70s, Chong had been working in Singapore at a poultry centre, using his money to supplement his mother’s and sibling’s school expenses. Upon returning to Malaysia in 1978, he began work in construction, started a family, yet still struggled to make ends meet. A friend from Singapore told him of an opportunity for some transporting work; and while he felt uncomfortable with the work, he was persuaded by the financial support that this could mean for him and his family.

At the time, Chong’s youngest son was three years old: the lack of money and living conditions he now faced reminded him of his own as he grew up, where his mother had to give away his youngest sister to ease their living costs. Thinking of the burden of his child growing up fatherless, 26-year-old Chong accepted the trafficking job, hoping this would turn his fortune around.

In the morning of his arrest, Chong received a call from his friend to pick up a package. When he got there, the police came down on him, seemingly expecting him; and while his friend – the one who originally brought him into this deal – managed to escape, Chong was left alone with the package. He was arrested and taken to Simpang Renggam Prison, and later sentenced to death in Johor Bahru High Court.

The case

Chong’s family has been working to get his case heard: they’ve endlessly reached out to lawyers to pick up their case, submitted multiple pardon petitions over the years to the Malaysian King. They have even hand-delivered an appeal for clemency to the former king in 1995. All were unsuccessful.

Dobby told TalkingDrugs on how the case reached ADPAN indirectly in 2021: a Buddhist association, which had held the case for almost 20 years, recommended ADPAN to the family. It was first met with surprise: how had someone stayed in death row for so long, without ever legally challenging the sentence? And while there had been a minor unsuccessful attempt at a prison escape, Chong’s case seemed to have simply stagnated. This was not aided by the fact that while the family had appealed for clemency informally, there had never been a formal request for clemency, meaning Chong’s case had little registered judicial activity throughout his 34 years of imprisonment.

Regardless, ADPAN dug into the case, looking to see what they could do for Chong. The lack of clemency appeals was a useful starting point; the fact that Chong had had no medical visits for many years was another. When Human Rights Watch facilitated a medical visit after he complained of some persistent neck pain, they discovered that Chong had stage IV throat cancer – which, as tragic as it is, pragmatically helped his case for release.

“It’s really strange why he was there for so long. But terminal illness should be enough to get you off death row”, Dobby told TalkingDrugs.

The appeal

Support for using the death penalty for drug-related crimes has not been incredibly high in Malaysia: a 2013 study by the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty showed that between 25% and 44% of polled individuals supported a mandatory death penalty, depending on the drug and the amount necessary to possess. 30% of those polled were against the mandatory death penalty for any crime.

Ending this practice will primarily benefit people arrested for drug-related crimes: according to HRI’s report on the use of the death penalty in 2022, just over 67% of people in Malaysian death row were there for drug-related offences (903 out of 1343).

However, strong political opposition and advocacy by civil society organisations against the death penalty has progressed efforts to abolish this practice. Just last year, the Malaysian government confirmed their intentions to abolish the mandatory death penalty. This still maintains the practice, as well as the potential use of life imprisonment sentences instead.

It is within this context that ADPAN pursued the route of regal clemency. The King has the power to grant clemency to whoever, whenever he wants: this power is often used around public holidays in Malaysia. The advantage of pursuing this legal route is that there is no limit to how many times you can apply. The King’s decision is also informed by a council composed of political and health figures that can inform the clemency decision, creating opportunities for political advocacy.

ADPAN found a champion for their case in Marina Ibrahim, a member of the Democratic Action Party, and state-level lawmaker of Chong’s home-town. Ibrahim helped bring Chong’s case to the King’s council’s attention, which was ultimately overturned, helping release Chong after 36 years in prison, and 29 years in death row.

The legacy

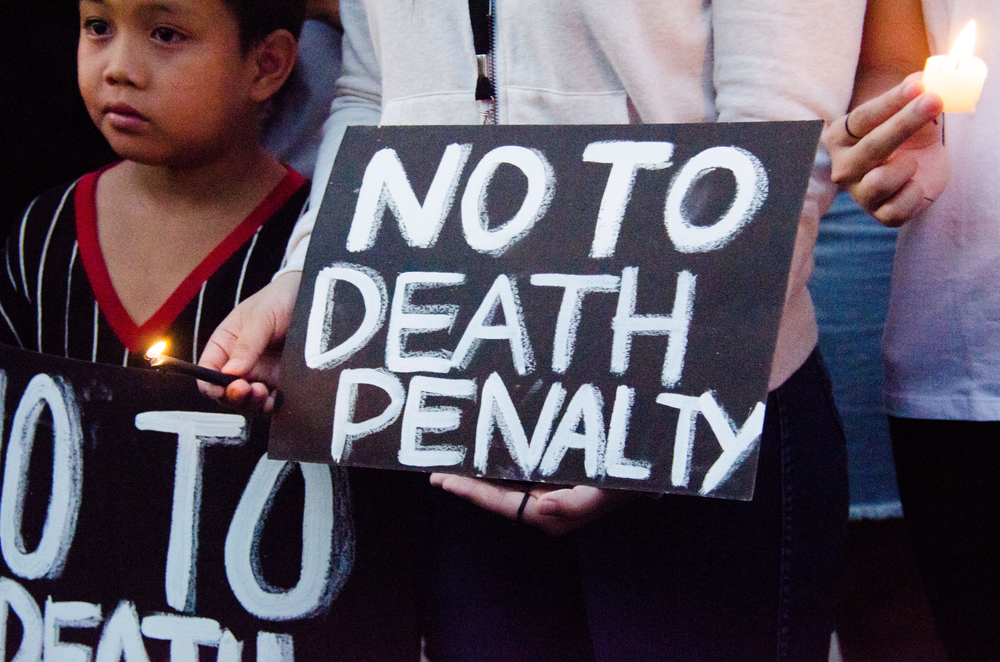

Dobby has said that ADPAN will continue working hard to abolish the death penalty, especially for foreign nationals who don’t have the same access to legal channels that locals can access. While shocking, Chong’s story is an example of how sustained and expert challenges to the death penalty can change the lives for people thrown into death row. ADPAN is working on overturning more death row cases by working with incarcerated people with health conditions.

There are new laws that may take people off death row: the Government introduced legislation in April repealing mandatory death sentences, although it has not been completely abolished. This will create a new framework where judicial decisions are given to judges; it’s intended to reduce the number of people on death row, where 1,300 people are estimated to still be there today.