For many years, international drug policy seemed stuck in tired rhetoric about a ‘drug-free world’. International discussions repeatedly called for consensus, compliance and conformity with prohibition, while the global number of people who use drugs continued to rise to record-high numbers. In recent years – as first spotted by the late Professor Dave Bewley-Taylor in 2012 – this conservative consensus seems to have fractured. What’s happened, and why?

The UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) is one of the best places to see how countries’ positions on drugs differ from each other. At the 2024 UN CND meeting we saw, for the first time since 1992, a vote take place on a resolution – a watershed moment after decades of consensus decision-making that stifled reform. In 2024, as well as the usual official declaration, there were two opposing joint statements: one led by Colombia, and one by Russia. The Colombian statement called for respect for human rights, gender equality, indigenous rights, and support for harm reduction. The Russian statement called for harm prevention (meaning abstinence) instead of harm reduction. The split in international drug policy became even more obvious at the 2025 CND meeting where several votes occurred, leading to a decision to review the very structure of international drug policy.

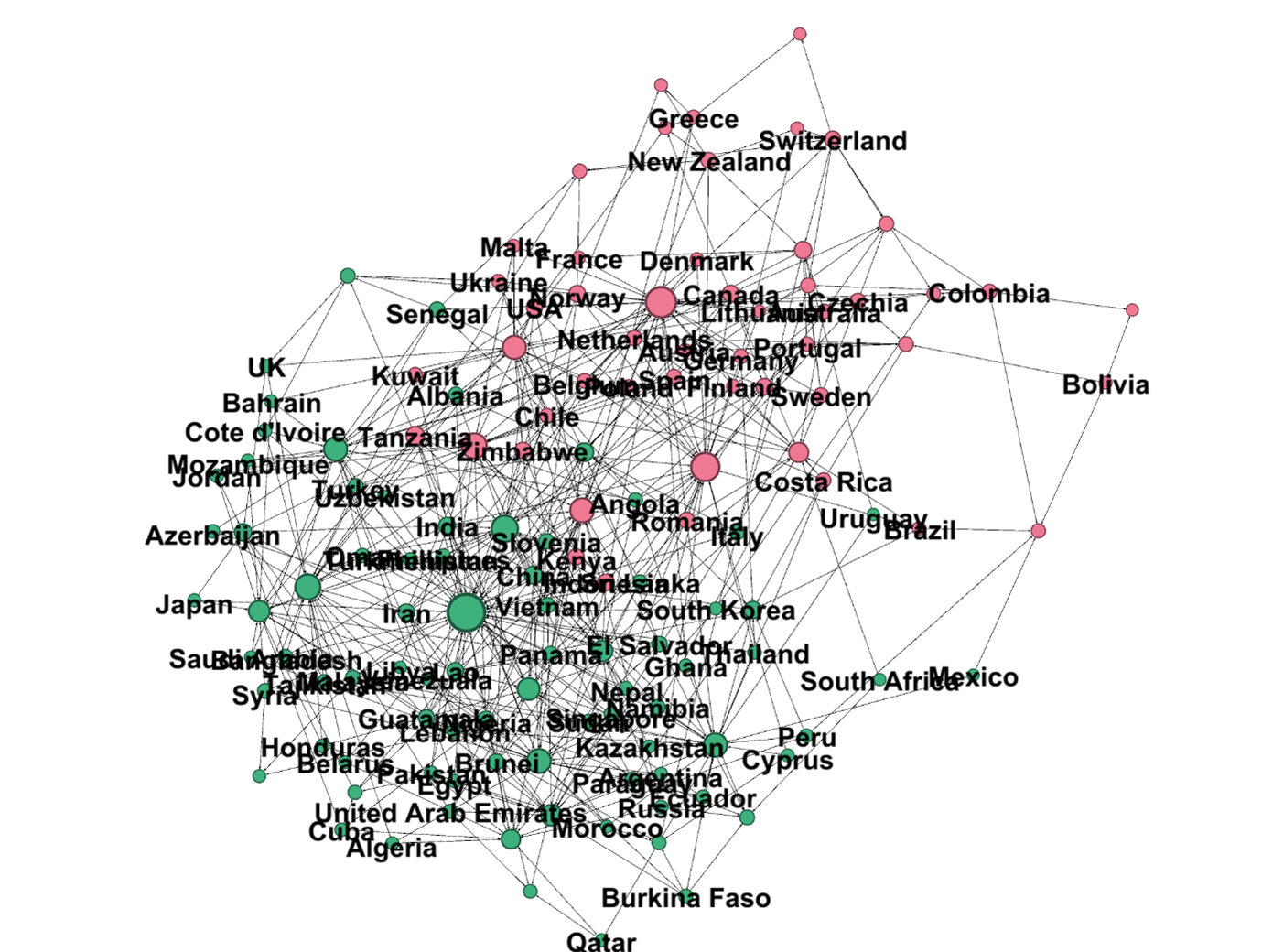

To explain how and why this fracturing occurred, Felipe Krause, Martin Bouchard and I studied the statements that countries made at the 2024 CND, as such statements are a good indication of their national stance on drugs. We examined which countries supported policies like harm reduction, the right to health, and ‘evidence-based policy’, and which supported more conservative policies like drug seizures, border control, and ‘zero tolerance’ approaches.

The policy constellation

By connecting countries to the policies they supported, we drew the diagram below. The green dots at the bottom left form a constellation of countries and policy positions that we describe as ‘traditionalists’. These nations supported the traditional, prohibitionist interpretations of the international drug conventions. Most of the countries of Africa, Asia and the Middle East are in this constellation.

On the other, represented by the red dots at the top right, is the constellation of more ‘liberal’ countries and policy positions that were more in line with progressive reform drug policy reforms. In this constellation, we find most of the countries of Western Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand.

We also found a moderately strong correlation between their choices to sign up to either of the joint statements led by Colombia or Russia, and where they fell between the liberal and traditionalist constellations we identified. This is a strong indicator that a real divide has opened up in international drug policy between traditionalist and liberal positions.

Why countries’ stances on drugs differ so much

Our next step was to try and explain why countries split in this way. The tendency of different countries’ populations to hold different moral beliefs has been studied for many years by the World Values Survey (WVS). We used data from the most recent wave of the survey to explore whether the values that are held by countries’ populations can explain the positions taken by their representatives at the CND.

What we found is that the dimension of moral values that are described in the WVS (which run from ‘emancipation’ at one end to ‘obedient’ at the other) play an important part in explaining which countries supported which policy positions. Emancipative values align with the belief that people should be free to decide what they want to do, with minimal state interventions. Countries with higher levels of emancipative values were usually in the liberal constellation. Obedient values align with belief in the importance of social conformity. Countries whose populations show greater preference for obedient values were usually found in the traditionalist constellation.

We say “usually”, because there were some notable exceptions. Latin American countries did not follow this pattern. Most of them are near the middle on the emancipative/obedient dimension of moral values. Recent research shows that Latin American governments’ drug policy positions tend to be influenced by whether they have a left or right-wing government at the time. This might also explain why we found the UK and Italy in the traditionalist constellation at the 2024 CND, and why the USA switched sides. In 2024, the US delegation to the CND supported liberal policies and proposed the resolution that specifically endorsed harm reduction. At the 2025 meeting, after the re-election of President Trump, the US delegation attempted to block all progress towards more liberal drug policies.

Our analysis points to an explanation of why the international drug policy consensus has fractured. Since the early 1980s, the WVS has shown a fascinating trend in the values held by the populations of some countries, especially those that have been described as WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, Democratic). This acronym applies to many of the countries we found in the liberal constellation in international drug policy.

A study into different WVS waves showed that people in WEIRD countries have become more morally emancipative, while other countries have not. This has led to a growing divergence in the moral beliefs held by people across different types of countries. This may help to explain why some more emancipative countries have peeled themselves away from the prohibitionist consensus.

Of course, other factors are at play in causing change in drug policy positions, such as geopolitics, and the actions of civil society organisations like those that are brought together by the International Drug Policy Consortium. The election of authoritarian populists in liberal democracies shows that progressive change is neither inevitable nor irreversible. But if the trend continues of international divergence on basic moral values, then we can expect to see even more fracturing in international drug policy.

Our research paper can be read here.