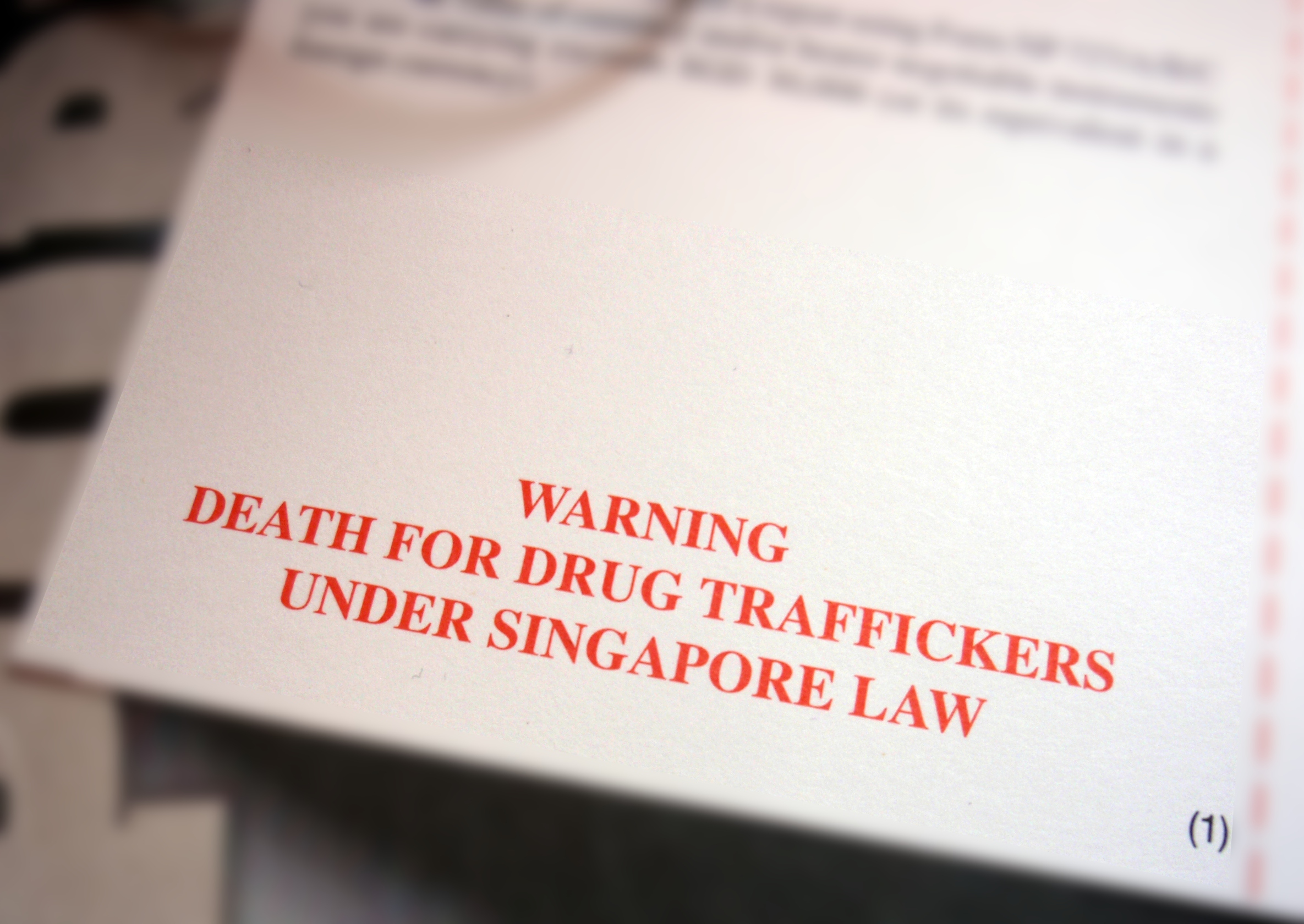

The atrocities of the world drug war are often so brutal that they become like a parody of themselves: sinister illustrations invented in Singapore for children come to mind, or recent news that all the men living there were executed in an Iranian village in the name of drug control. The most recent news of this kind that inspires concern and surprise took place on April 20 in New York at the UN General Assembly Special Session on the World Drug Problem, where the Russian delegation was holding a round table on science. For knowledgeable observers, it was like attending a global warming event hosted by climate change deniers.

Russia is one of the countries most vehemently denying the scientific validity of effective drug dependence treatment. Russia has banned the use of methadone and buprenorphine, widely studied drugs that the World Health Organization considers critical for the treatment of addiction to heroin and other opiates. Instead, Russian “narcology” (a sub-discipline of psychiatry dealing with the treatment of drug addiction) supports treatments such as “coding”, in which patients are subjected to hypnosis, during which they are told that the use of alcohol or drugs will lead to their poisoning and death, as well as the method of introducing the patient into a coma followed by electroshock therapy. Scientists in St. Petersburg have tried an approach adapted and practiced in China, which involves drilling holes in the skull and removing parts of the brain thought to be associated with drug cravings. The consequences of such “neurosurgery” are irreversible, and the practice raises the same ethical questions as lobotomy, which was actively used to treat mentally ill patients in Europe and the United States in the 1930s and 1940s.

After speeches by eminent scientists who spoke at the UN about the basic principles of drug addiction treatment, a representative of the Russian Ministry of Health told the audience that methadone therapy “is not suitable for us”, because. in the country, the method of substituting one drug for another is not considered effective. But she did not mention that at home in Russia, scientific research and conclusions of scientists that run counter to this official position are aggressively challenged. Prosecutors intimidate researchers trying to spread information about methadone, and websites that post information about the drug are blocked by the Federal Drug Control Service.

Russian laws prohibit the presence of even a tiny amount of poppy straw or traces of opium poppy alkaloids, which can be found, for example, in poppy seeds, while their presence in a consignment makes the entire consignment illegal. These laws have recently resulted in a confectionery importer being accused of drug smuggling. After Olga Zelenina, a respected scientist and head of a laboratory at the Penza Agricultural Institute, confirmed that poppy seeds may contain traces of opiates, she was arrested by a group of armed drug control officers, and then Ms. Zelenina was charged with “aiding and abetting the intentional act of drug trafficking”. Moscow decided it was best to support research into the mind-altering properties of parsley seeds. The seeds were then banned by Rospotrebnadzor in 2011.

Russia is ignoring the fears, both of international experts on drug addiction and of its own health professionals, that a refusal to accept internationally recognized treatments results in an increase in new HIV infections and deaths. So what does this country want to achieve when it hosts a science session at a major international meeting on drugs? Or when Russian diplomats during the negotiations at the Commission on Narcotic Drugs in March, according to the participants, demanded that any references to “evidence-based approaches” be replaced with the phrase “scientific approaches” in UN documents? Such an appeal to science seems to be a way to prevent non-profit organizations from being heard not only in their own country, but also on the international stage.

Russian human rights activists have been really busy documenting the results of drug policy in Russia, and the results are horrendous. Several patients who were denied methadone treatment are currently suing the Russian government at the European Court of Human Rights. Other groups of Russian human rights defenders, who are forced by law to call themselves “foreign agents” when receiving financial support from abroad, still continue their activities to challenge government statements and document cases of violence, denial of medical care and other violations in drug dispensaries, prisons and police detention facilities. It is precisely this kind of evidence that Russian officials, who insisted that participants in the recent AIDS conferences in Moscow followed “approaches consistent with Russian ideology”.

As for the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, the agency that selected applications for hosting side events at the UN Special Session and was also the coordinator of the Russian session, it’s hard to imagine what they were thinking there. The agency is headed by a diplomat from Russia, and apparently the possibility of holding such an event was an offer that could not be refused.

Side events, by definition, are not significant events. But in a UN system that operates by consensus, the opinion of any country in the Special Session of the General Assembly can reduce the outcome of the entire discussion to the lowest common denominator. Russian diplomats managed to remove any mention of methadone or buprenorphine from the final document adopted on the first day of the Special Session, and Russia was one of the countries that included the phrase “in accordance with national legislation” in the document in order to give themselves the opportunity not to comply with the norms recommended based on global consensus.

As the world begins to prepare for the next UN drug debate in 2019, UN staff and representatives from all countries must understand that Russia’s understanding of science falls short of international standards. As for the Russian event at this Special Session, dedicated to science and drug addiction, I would like it to be placed in the program in the “tragicomedy” section.

Source: medium.com and Andrei Rylkov Foundation for Health Protection and Social Justice