The fate of a harm reduction organisation in Atlantic City, New Jersey is up in the air.

Local lawmakers of the beachside tourist town, where the vast majority of residents are people of color, are considering the deauthorisation of the Oasis Drop-In Center, the single SSP in the city and one of seven in the entire state. Ordinance No. 7-D is currently making its way through the legislative process in the City Council. On June 16, it won majority approval (7-2) in the Council’s first vote. A second vote is expected on July 21, according to an activist with knowledge of the matter. If passed, the Oasis Drop-In Center will be forced to close within less than two months (50 days) of the passage of the city ordinance, according to the proposed law.

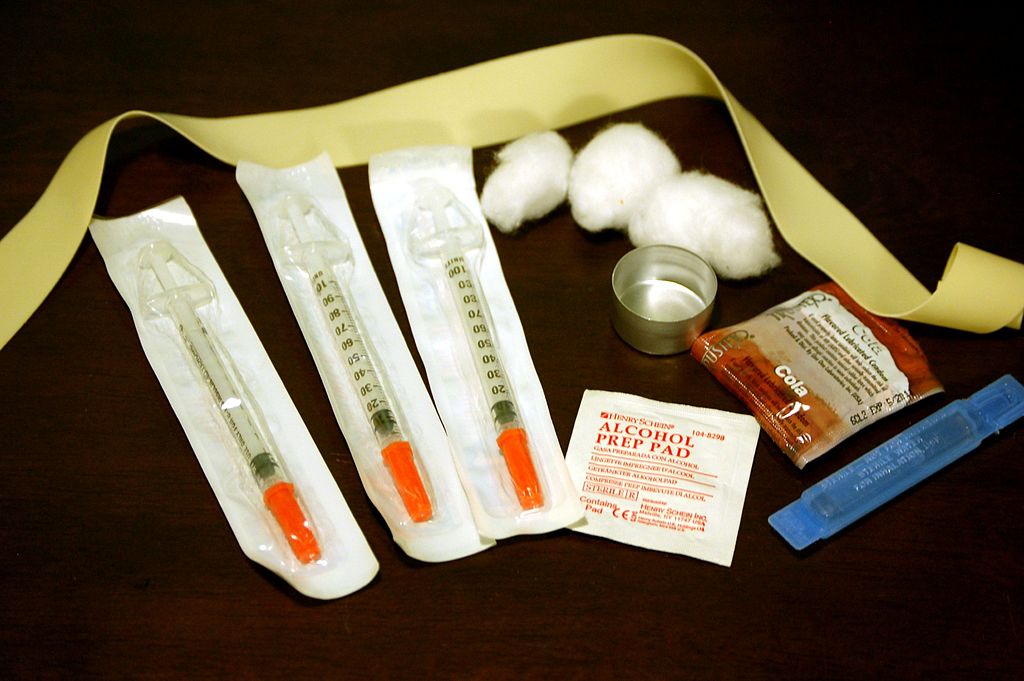

Politicians and cynical community members claim syringe litter is part of what’s driving their effort to shut down the SSP. But two Council Members opposing the deauthorisation disagree with the claim that Oasis Drop-In Center is populating streets with the sharps. “Before the needle exchange, what I can tell you is our streets were flooded with needles and drugs, flooded,” Dunston told The Press of Atlantic City. “Can I tell you that I see the same flood now in Atlantic City that I saw back then? Absolutely not.” There’s also much evidence that demonstrates SSPs actually reduce syringe litter, as the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recognised. The latest data, published on the City’s website on May 7, shows that Oasis Drop-In Center has a lifetime return rate of 92% for syringes.

Proponents of the ordinance also falsely claim that the SSP mostly serves out-of-towners. According to internal data, the majority of participants are Atlantic City residents.

The need for the services is great, as is seen in the other regions across the country seeing anti-SSP attacks. Atlantic City’s county is one of the jurisdictions hardest hit by new HIV diagnoses, driven by injection drug use. In the city with the sixth most reported naloxone administrations in New Jersey, according to Health Department data, the number of fatal overdoses leapt from 171 to 216 deaths between 2019 and 2020.

Although the state Department of Health did not voice outright opposition to the proposed ordinance, the agency did tell TalkingDrugs that the services are necessary. “The Department of Health recognises the importance of continuing harm reduction services in Atlantic City, which provides much more than syringe access,” said New Jersey Health Commissioner Judith Persichilli. “These centers support the overall health and well-being of people who use drugs through linkages to drug treatment, care, housing, overdose prevention and other vital social services.”

Not all politicians in New Jersey are hostile towards SSPs. The state legislature has introduced legislation that, if passed before the City Council vote, would block the likely deauthorisation of the Oasis Drop-In Center. The bills (S3009/A4847) would move the authority to establish or terminate harm reduction services from municipal bodies, like the Atlantic City Council to, solely, the state Health Commissioner. Additionally, it would expand services beyond just the state’s few programs.

***

While the SSPs in West Virginia, Indiana, Michigan, California, Washington, and New Jersey have been closed or are about to be closed by lawmakers, SSP opponents on the West Coast are taking a different approach. In college towns in northern California, two programs have been targeted by litigation, pursued by the same lawyer. On August 18, 2020, Northern Valley Harm Reduction Coalition (NVHRC) of Butte County was forced to shut down after a settlement was reached with the 20 plaintiffs, a number of whom are local businesses. The California Department of Public Health (CDPH) was also a part of the settlement: they too had been sued in the same lawsuit, in their case for allegedly erroneously authorising the NVHRC.

The lawsuit weaponised claims of syringe litter against NVHRC, similar to other assaults on SSPs. In this situation, though, the plaintiffs exploited a California environmental protection law (not designed to address SSPs) to demand that a judge halt the program’s operations, claiming NVHRC “spreads thousands of used and unused hypodermic needle ‘litter’ though-out the parks, the residential landscape, the public places, and the business environment of Chico and Butte County.”

In the same month that NVHRC settled with the group of SSP opponents, a harm reduction organisation a few hours south of them was certified by CDPH. But just four months later in December 2020, the Harm Reduction Coalition of Santa Cruz County (HRCSCC) was sued by current Santa Cruz City Council Member Renee Golder, the former city police chief, a neighborhood association, and two community members. Councilmember Golder did not respond to TalkingDrugs’ request for comment.

The coalition is demanding the harm reductionists turn over internal documents, including the contact information of every volunteer and the available home addresses of participants, as part of the litigation. “We're trying to beat this. But they're trying to suck the resources out of us and dox us along the way,” Dani Drysdale, an HRCSCC staff member, told TalkingDrugs. She is hopeful that HRCSCC will prevail against the lawsuit. The plaintiffs will have to prove that HRCSCC itself is the direct cause of syringe litter, and not the factors found by a Santa Cruz Health Services Agency study to be driving improper disposal, namely lack of accessible disposal sites and fear of law enforcement.

California state lawmakers, like New Jersey’s, are working to halt localities from shutting down SSPs. Prompted by the 2020 lawsuits in Butte County and Santa Cruz, as well as a 2019 case in Orange County, Assemblymember Joaquin Arambula introduced bill AB-1344 in February 2021 to remove the currently-required environmental review that’s been “weaponised,” as he writes in a June bill analysis, “to thwart sound public health policy.”

“I authored Assembly Bill 1344 to protect these services from litigious efforts to dismantle these programs by using the California Environmental Quality Act, more commonly known as CEQA,” Assemblymember Arambula told TalkingDrugs. The bill has already been approved by the Assembly, and now must survive the State Senate Committees, a floor vote, and Governor Gavin Newsom. “ I will continue to push for AB 1344 because this is a public health issue, and the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated our looming opioid public health emergency.”

In the bill’s analysis, he emphasised the stakes of the matter: “Without immediate legislative action, the public health prevention services provided by SEPs directly authorised by CDPH will be curtailed, and new programs will be deterred, at the precise time when the need for them is increasing.”

***

The most high profile legislative attacks on SSPs since the pandemic began have been deauthorisations. Yet all-out pre-emptive bans have flown under the public’s radar.

Jurisdictions that had already successfully shut down SSPs years prior took action during the pandemic to prevent the future return of life-saving services to their area. Two small cities outside of Los Angeles in the conservative Orange County adopted ordinances in 2020 outright banning storefront or mobile Syringe Exchange Programs, as they’re called in California. First came Anaheim’s Ordinance No. 6490 in July, and then Santa Ana’s Ordinance No. NS-2996 in October. In the years prior, the localities passed ordinances and won a CEQA lawsuit against the Orange County Needle Exchange Program, effectively revoking its existing state approval to operate in the two cities, as well as the neighboring Orange and Costa Mesa, the latter of which banned SSPs in 2019, while the former has limited such programs to mobile sites.

A different approach: North Carolina legislators are pushing a bill that effectively bans SSPs through highly burdensome restrictions. For one, Senate Bill 607 straightforwardly would ban mobile sites. Fixed sites, on the other hand, would face a slew of stringent requirements, along with the revocation of participants’ limited criminal immunity for possession of syringes and needles if they are near a school. The following would be required of all SSPs:

- Located in “a facility that offers professional or rehabilitation services for individuals with drug use disorders”;

- Located or relocated outside a three mile radius of school zones;

- Obtain the support of half of all residents, if located in a residential neighborhood;

- Have no staff members with pleas or convictions for misdemeanor drug offenses;

- Maintain $1 million worth of professional liability insurance coverage at all times;

At the time of publication, the bill has failed to pass either chamber of the state legislature. The bill’s primary sponsor, Senator Joyce Krawiec did not respond to TalkingDrugs’ request for comment.

***

Harm reductionists are not letting SSPs close without a fight.

“Harm Reduction activists have organised in several ways to push back against SSP closures and restrictive laws,” Paul LaKosky, executive director of the North American Syringe Exchange Network, told TalkingDrugs. “Organisations like the Drug Policy Alliance, National Harm Reduction Coalition, NASTAD, and others have conducted policy initiatives to affect change on a national level. Locally, harm reduction proponents have engaged community support among recovery communities, drug user unions, community coalitions, etc. to lobby state, county, city (local) governing bodies for the rights of people who use drugs to access health services.”

This type of resistance has long been the norm of harm reduction work. “Harm reduction activists and SSP workers are doing what they always do,” said Drew Gibson of AIDS United, “namely running drug user health programs in often hostile political environments, with way too little funding and an ever-increasing need for their services.”

One example of legal resistance is with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), a legal advocacy organization that successfully paused the roll-out of the anti-SSP West Virginia law. On June 25, the legal advocacy organization won a temporary halt to the law. A hearing further considering the issue will be held on July 8, just a day before the law was to take effect. The director of the state’s ACLU chapter told the Associated Press that the ruling was “encouraging.”

But Gibson is unsure that the grassroots power of pro-SSP advocates is enough to protect life-saving services.

“The amazing folks in Scott County got a whole roster of public health officials—including former Surgeon General Jerome Adams—and doctors and nurses and concerned citizens and people in recovery together to try and save their SSP, which was created in direct response to the largest injection drug use-fueled HIV outbreak in the US,” said Gibson, “and it didn’t work.”

The stakes are too high for SSPs to continue to be shut down.“If this trend of SSP closures continues—and what has happened in the past continues into the future,” Gibson said, “people who use drugs and the people who love them will continue to suffer until some infectious disease outbreak or overdose spike gets so bad that elected officials who are opposed to SSPs are forced into some semblance of positive action.”

“We cannot allow this cycle to continue.”

*Sessi Kuwabara Blanchard is an independent drug journalist and transgender critic. Previously, she was the original staff writer at Filter, an online publication dedicated to covering harm reduction and drug policy. Follow her on Twitter, @SessiBlanchard.