As the COVID-19 pandemic hit the world last year, governments executed far fewer people for drug convictions than they did in 2019. A new report from Harm Reduction International (HRI) details this decline—as well as the seemingly contradictory fact that governments sentenced more people to death for drug charges in this period.

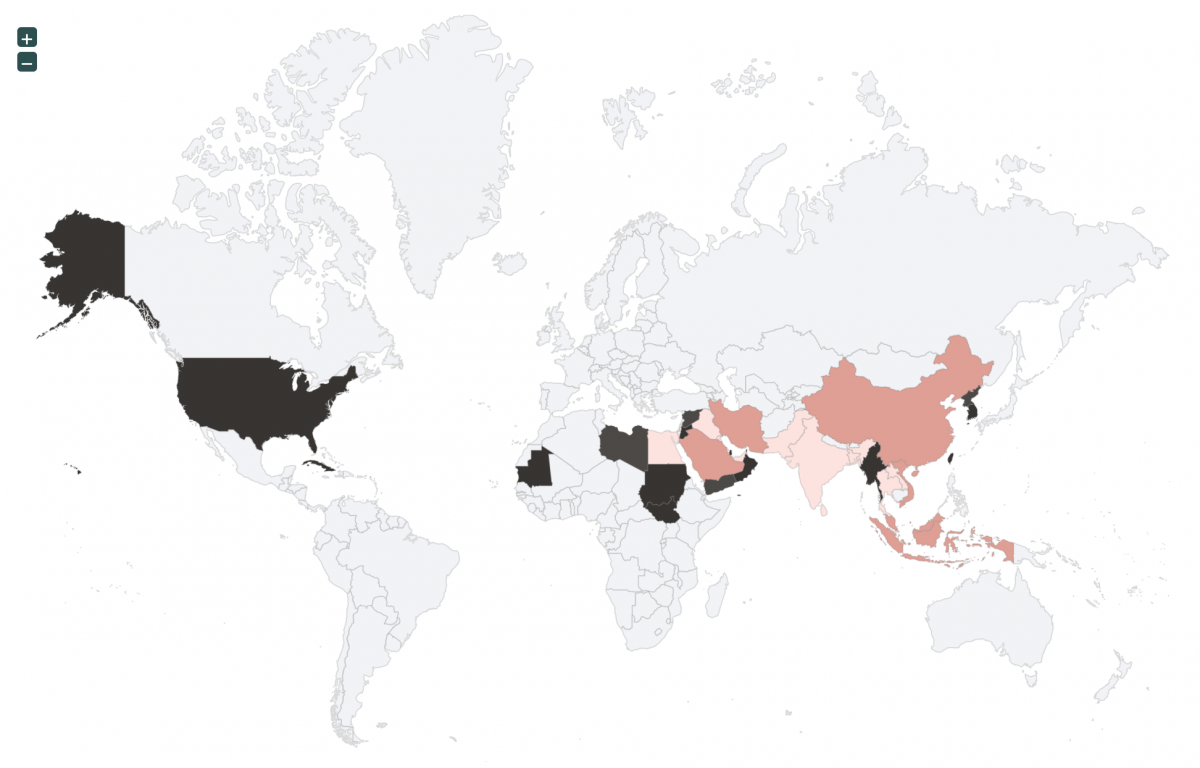

A total of 30 people were officially recorded as being executed for drug convictions in 2020, according to the report. This was a 75 percent drop from 2019, and is the lowest point observed since HRI began tracking in 2007. Just three countries—China, Saudi Arabia and Iran—carried out these recorded executions.

But even as executions dropped, death sentences for drug charges actually increased from 2019—with 10 countries sending a total of at least 213 people to death row in 2020, a rise of over 16 percent. Add to that the fact that more countries are considering reinstating laws to execute people for drug convictions, and it’s clear this fight is far from over.

“Globally, the sentiment towards the death penalty for drugs does not improve,” co-author Ajeng Larasati of HRI told Filter. “We could not confirm to what extent COVID-19 played a role in the decrease, but the pandemic has slightly shifted the government’s focus away from executions, and the restriction put in place in some countries might also serve as a challenge in carrying out an execution.”

State Secrecy in China and Vietnam

As HRI cautions, we don’t actually know the true number of deaths globally. Both China and Vietnam are reported to execute people for drug convictions on a regular basis, but state secrecy laws prevent collection of reliable data.

We know this much: China remained the top executioner worldwide for drugs in 2020, even on the basis of its official figures. The death penalty and drug convictions are highly intertwined in the country, with most executions being drug-related. Nearly half of all drug cases tried in court are believed to result in a death sentence—Chinese criminal law applies it to drug smuggling, selling, transporting or manufacturing—and it’s not unusual for courts to execute people immediately after they receive the sentence.

In most countries, a defendant will at least have the chance to appeal their sentence. In Vietnam, evidence suggests that nearly 80 people were sentenced to death for drugs in 2020, although secrecy prevents their inclusion in the official worldwide total. Hundreds of people received death sentences overall that year, according to the HRI report—so many that prisons are “overloading” and governments are now building new facilities and execution sites.

Saudi Arabia’s Moratorium, Singapore’s Pause

At the opposite end of Asia in Saudi Arabia, a major development could shake the global drug execution regime. The country saw a massive, 94 percent drop in drug executions since 2019. This was due to political reforms put in place by Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman (MBS)—who perhaps needed to deflect attention from his role in an ongoing genocide in Yemen and the grisly assassination of a Washington Post journalist in Istanbul.

Early in 2020, MBS announced a ban on drug executions, and in August announced that he was “revising penalties for drug-related crimes and that a decision to abolish capital punishment for such offences was expected ‘very soon.’”

Despite this, five people were executed for drugs in Saudi Arabia in January 2020—including an Egyptian national who was severely tortured, and whose arrest and execution was hidden from his own family.

As HRI cautions, Saudi Arabia’s progress may be short-lived. Much like a US presidential executive order, MBS’s reforms are not yet enshrined in law and can be easily reversed by himself or his successor. And even as the country banned executions, it hasn’t stopped people being sentenced to death. Death row thus continues to grow, though we don’t know how many people it holds.

Another Asian country reached a notable milestone: Singapore executed no one for a drug conviction in 2020, for the first time since 2013. While the government continues to strongly defend the death penalty, lawyers and civil advocates fought hard to halt any executions.

In a promising sign, the nation’s Court of Appeal (similar to the US Supreme Court) overturned a death sentence for drugs on review, for the first time ever. This may provide legal precedent to prevent future executions. Generally, Singapore has some of the most brutal drug laws in the world. The death sentence is mandatory in cases of drug trafficking, and you can in theory be put to death for having less than a pound of marijuana.

Worrying Prospects

As the HRI report shows, the good signs from 2020 may be illusory. Singapore’s maritime neighbor, Indonesia, also executed no one for drugs last year. But it sentenced 115 people to death for drugs between October 2019 and October 2020—a 62 percent increase from the prior 12 months.

HRI estimates that worldwide, at least 3,000 people are on death row for drug convictions. This in itself is a human rights travesty, as most people on death row are detained in solitary confinement with few options for human contact or exercise. People incarcerated under these conditions may also be denied decent food, water or medical care.

And at least one more country may soon be adding to the toll: The Philippines, under President Rodrigo Duterte, which has long been orchestrating a campaign of extrajudicial killings, is considering officially reinstating the death penalty for drug charges. The nation’s Congress introduced at least 23 new bills last year to execute people for drug possession or sales.

“The abolition of the death penalty is a result of collaborative work between stakeholders in the country,” said Larasati. “But, more often than not, it happened with support from political leaders. Such political leadership comes because advocates present compelling evidence—often in collaboration with media, academia and religious leaders—that the death penalty does not have a deterrent effect, and it is irreversible, often clouded with discrimination and rights violations.”

This article was originally published by Filter, an online magazine covering drug use, drug policy and human rights through a harm reduction lens. Follow Filter on Facebook or Twitter, or sign up for its newsletter.

* Alexander Lekhtman’s journalism covers the policy, science and culture of drugs. His journey began as an activist with Students for Sensible Drug Policy at New York University, where he served as president, helping organize marijuana legalization and “Ban the Box” campaigns. He was also an organizer for the 2017 New York City Cannabis Parade. His drug journalism career began in 2016, and his work has been published in High Times, Leafly, Merry Jane, AlterNet, Psymposia and Psychedelic Times. Alexander was previously Filter‘s editorial fellow.