The Johns Hopkins University and The Lancet Commission on Drug Policy and Health conducted a study of new scientific evidence regarding the public health problems that arise as a result of the current drug policy based on the principles of the war on drugs and “zero tolerance” for drug use. In his article “Public Health and International Drug Policy”, published in The Lancet on March 24, 2016, members of the Commission aimed to draw the attention of the international community to the existing evidence in the field of health during discussions on drug policy, such as the debate during the 2016 UN General Assembly Special Session on drugs. The article notes that the commission is concerned about the fact that drug policy laws and regulations are often influenced by ideas about drug use and addiction that have no scientific basis .

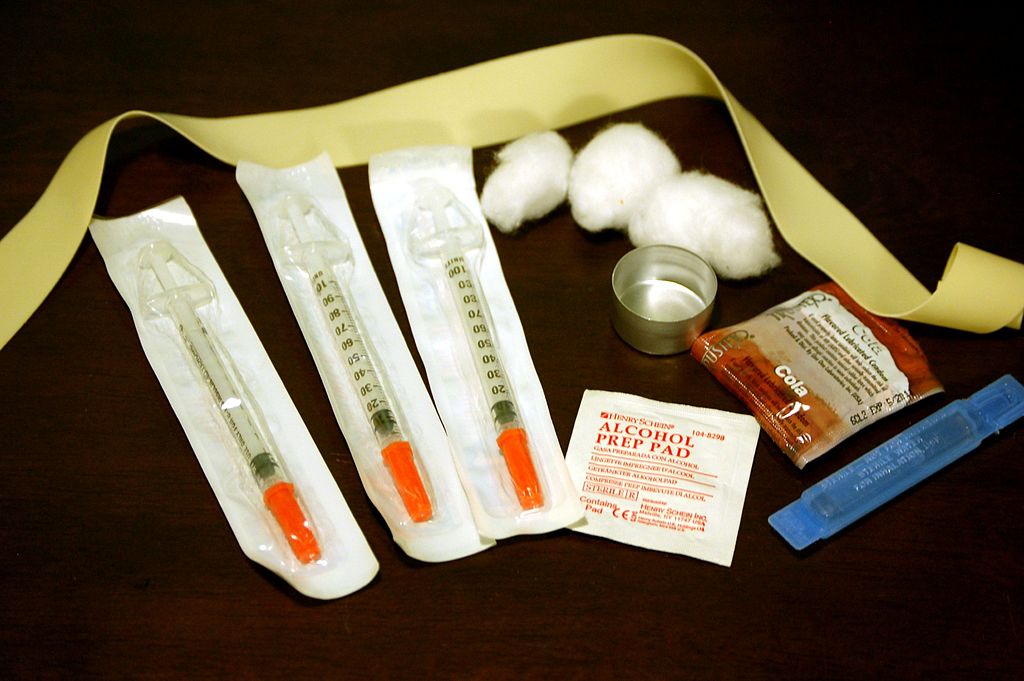

Among the key findings of the members of the Commission was the conclusion that the policy of total prohibition of drugs has created a shadow economy run by criminal circles, and repressive drug policies greatly increase the risk of HIV transmission by injection. In many countries of Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EECA region), law enforcement activities are a direct barrier to the provision of services such as syringe and needle exchange programs (SEPs) and opioid substitution therapy (OST) programs. Law enforcement agencies, in an effort to dramatically increase arrest rates, target locations where services are provided and locate, harass and detain large numbers of people who use drugs. Moreover, the Commission concluded

Often there are no national standards for the quality of drug dependence treatment, and there is no regular monitoring of practice. In too many countries, under the guise of treatment, patients are offered beatings, forced labor, lack of medical care and proper sanitary conditions, including detention in detention centers that look more like prisons than treatment centers.

The main problem specific to the EECA region, the Commission calls the transmission of HIV associated with injecting drugs using non-sterile equipment. The prevalence of HIV infection among people who inject drugs is many times higher than among the general population in many countries.

Chart 1 : HIV prevalence among people who inject drugs and the general population

Shown are countries where more than 30,000 people inject drugs. Data for people who inject drugs are shown from 2009-2014, for the general population from 2014 Source: UNAIDS, GAP report, 2014.

By some estimates, 30% of all HIV transmission is associated with unsafe injections. Injecting drug use is a more important determinant of HIV transmission in EECA than in any other region of the world. And while the number of new HIV cases worldwide fell by 35% between 2000 and 2014, the number of new cases in the EECA region increased by 30% over the same period – in this region, unsafe injection use accounts for more than 65% of the cumulative number cases.

The authors of the article emphasize the effectiveness of the widespread introduction of substitution therapy programs, as it helps to stabilize the lives of all who are program clients, and as a prevention of HIV and hepatitis C, since it excludes injections. In 2012, a meta-analysis of studies from Europe, North America and Asia concluded that oral OST and methadone maintenance in particular reduce the risk of HIV transmission among people who inject opioids by approximately 54%.

Despite the limited body of evidence on the efficacy and cost-benefit of opioid agonist substitution therapy, some countries are pushing for more research to be done in their country settings before scaling up OST programs. For these and other reasons, in some countries ST is in a state of permanent pilot launch, and in countries from the EECA region, service coverage, quality and accessibility of SEP programs are generally insufficient, and access to ST is limited or non-existent.

Studies in a variety of settings have shown that opioid agonist treatment also increases adherence to ART among people who use drugs. In Ukraine, patients with access to integrated and co-located ART and OST services had greater access to ART than those who received OST in non-integrated facilities.

Political resistance to harm reduction measures rejects strong evidence regarding their effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Mathematical modeling shows that OST, NSP and antiretroviral therapy for HIV, if all of them are available, even if the coverage for each of the interventions does not reach 50%, their synergy can lead to effective prevention in the foreseeable future. The data collected in this article suggests that if OST, NSP and HIV treatment programs are used simultaneously, their synergistic effect can compensate for shortcomings in insufficient coverage. In this case, if only needle exchange and antiretroviral therapy are available to reduce HIV infections by 50% over a period of 10 years, only about 30% coverage of both programs is sufficient. But if both ART and NSP and ST are available, A 50% reduction in new cases over the same period could be achieved with only 20% coverage of these measures. Therefore, partial coverage of OST, NSPs, and ART can provide effective prevention if very high ART coverage cannot be achieved, which can be particularly difficult in countries where people who use drugs are criminalized.

Figure 2 : Required expansion of OST, NSP and ART programs to achieve 30% and 50% reductions in HIV incidence or prevalence among people who inject drugs over 10 years in Tallinn, Estonia (A), St. Petersburg, Russia (B) and Dushanbe, Tajikistan (C).

Source: Adapted from Vickerman et al, 2014, with permission from Elsevier.

Studies also show that a country’s lack of access to OST programs contributes to an increase in opioid injection use, and the prohibition of safe injecting drug use sites under external supervision hinders harm reduction programs that are effective in reducing overdose-related deaths.

The researchers concluded that drug policy that rejects the extensive evidence of its own negative impact and approaches that could improve health outcomes is detrimental to all involved. Countries have failed to recognize and compensate for the harm to health and human rights caused by drug prohibition policies, and thus they have neglected their human rights obligations. These countries waste public funds on measures that have no visible effect on drug markets and miss opportunities to invest public resources wisely in health services that are proven to be effective for people living with drug addiction.

The Commission called on UN member states to make balanced political decisions in the field of drug policy based on the following recommendations:

- Decriminalize minor, non-violent drug offenses – use, possession and petty distribution and reduce the level of violence stemming from the fight against drug police.

- Ensure free access to harm reduction services for all who need them, recognize the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of expanding and strengthening services such as OST, NSPs, safe injecting drug use centers, and access to naloxone. Harm reduction services should also be available in prisons and detention centers.

- Make the category of people who use drugs a priority in the treatment of HIV, hepatitis C and tuberculosis, and ensure adequate services provide access to treatment for all who need it. Ensure the availability of humane and evidence-based drug treatment, including the expansion of OST programs in the community and in prisons. Reject involuntary imprisonment and violation of rights committed in the name of treatment.

- Provide access to controlled drugs and provide WHO with resources to assist the International Narcotics Control Board in using the best scientific evidence to establish the level of need for controlled drugs in all countries.

- Reduce the negative impact of drug policy on women and their families, especially by minimizing the length of time in prison for women, and develop appropriate medical and social support.

Indicators of health, development and human rights should be included in the system for evaluating the effectiveness of drug policy.

Gradually move towards regulated drug markets and apply scientific methods to evaluate them. As decisions are made, the Commission encourages governments and researchers to apply scientific methods and provide independent, multidisciplinary and rigorous assessment of regulated markets to draw lessons and build evidence in regulatory practices.

The Commission believes that by staying true to the declared goals of the international drug control regime, it is possible to have a drug policy that promotes the health and well-being of mankind, but subject to the input of medical science and the opinions of health professionals.

The full text of the unofficial Russian translation of the article is available online here

The original article is available online at The Lancet.

What is the Johns Hopkins and The Lancet Commission on Drug Policy and Health?

The Johns Hopkins University and The Lancet Commission, chaired by Prof. Adib Kamarulzaman of the University of Malaya and Prof. Michel Kazachkin, UN Special Ambassador for HIV/AIDS in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, is made up of 22 experts from a wide range of disciplines and professions in low-income countries. , middle and high income levels. We reviewed the global scientific evidence on the impact of drug policy on health, as well as our own analysis, including mathematical modeling, to further understand the complex and diverse interactions of drug policy on health, human rights and welfare.