As the sun set over an ancient riverside town in Iran, I was sat down with Sam (not his real name) and his mates for a picnic when he pulled out a vafoor – a traditional Persian opium pipe – and passed it to me. It left me with a warm, cozy feeling, kind of like smoking some good hash, but also heavy, like my body was suddenly weighed down with stones.

What made this encounter memorable was Sam’s profession.

“I joined the PAVA fifteen years ago, but for me it’s just a job I do for money to support my family, and then retire to a good pension,” he later told me.

PAVA is the domestic security branch of Iran’s national police force.

“My rank is like a detective in the PAVA. I catch the criminals, public enemies, bad people. But of course I’m like you guys; only I’m a policeman and I have to listen to my general.

I smoke hash, weed, sometimes vafoor, and I drink – as you know, it’s forbidden in our culture as well. I probably smoke more hash than when I started this job! We have all sorts of drink in our country: beer, whisky, vodka, sometimes arak [a grape-based liquor]. Not everyone’s like me – in our organisation we have some persons that don’t drink or smoke and are very religious – but there’s a few others like me as well, maybe 30-40%.”

I met Sam in the (slightly) simpler times of 2018 on my first trip to Iran. Since then, the country’s been rocked by two waves of mass protests against the ruling regime and a short war with Israel. At the time of writing, an uneasy ceasefire holds.

The USA briefly joined Team Israel, with President Trump’s chronically-online fingers typing about “regime change”. This claim brought back national traumas – even to those actively resisting against the Iranian regime – of the country’s struggles with foreign influence… which has also shaped its relationship with narcotics.

Opium and alcohol’s enduring history

Historically, both opiates and alcohol have always been a part of Persian society, with wine jugs being unearthed dating as far back as 5,000 BC. This didn’t change following the adoption of Islam after the Arab conquests. Despite occasional decrees that any Muslim caught imbibing would have molten lead poured down their throats, its prohibition never lasted long.

Opium was also used for centuries as a remedy against pain, diarrhoea and everything in-between. A popular Iranian pastime involved reciting poetry, opium pipe in hand. It was said to be hard to find anyone not using it, except perhaps during Ramadan.

In 1951, the democratically-elected prime minister Mohammad Mosaddegh believed Iran’s oil wealth should belong to Iranians, and pushed out Anglo-American corporations. The CIA and MI6 had other ideas; two years later, Mosaddegh was ousted in a coup that reinstalled the sidelined Shah (king of Persia) Reza Pahlavi as a despot.

The Shah’s legacy of prohibition

The Shah’s legacy was mixed. On the one hand, it brought about liberal, secular reforms: those viral photos of unveiled women walking the streets of Tehran are from his time. On the other, it was an repressive dictatorship where any group with dissenting ideas was outlawed and political opponents would be tortured in dungeons by the secret police.

Besides oil, the Americans were concerned with the steady stream of Persian opium trafficked worldwide. In 1955, poppy cultivation and opium use were both prohibited with harsh sentences. In 1959 even poppy seeds were banned, while America supplied the Shah with military hardware for counternarcotics operations.

Opium prohibition under the Shah was partly motivated by a desire to become Westernised: opium was seen as hangover of the backward, Oriental past, while the elites freely imbibed alcohol. Indeed, five thousand bottles of France’s finest produce were imported for the Shah’s grand festivities in 1971, celebrating the 2,500-year anniversary of the Persian Empire. Lasting three days and costing perhaps a billion dollars in today’s money, it may have been the most expensive party ever held, triggering widespread Iranian condemnation of the Shah’s extravagant lifestyle. The preacher Ayatollah Khomeini, who’d later lead the Islamic Revolution, called out the Shah’s hypocrisy of executing people for opium while still permitting alcohol.

Rather than international smuggling rings, those most affected were society’s poorest: nomadic tribes, vagrants and sex workers. Doubts appeared early on: two years into the counternarcotics campaign, the government declared an amnesty because its jails were too full. As a result of opium’s prohibition, heroin became a big business. It was more potent than opium, generated more profits, and took up less space when smuggled. Morphine and heroin factories appeared nationwide, leading to violent exchanges between police and smugglers. The Shah’s twin sister, Princess Ashraf Pahlavi, was allegedly busted with heroin in her luggage by Swiss customs but released under diplomatic immunity; his younger brother Hamid-Reza was also involved, and the best heroin in Tehran at the time was nicknamed heroin-e hamid-reza.

An innovative coupon system – soon overthrown

Fearing a heroin crisis and the loss of profits to Afghan and Pakistani dealers, Iran re-legalised opium in 1969. Under a ‘coupon system’, opium prescriptions were issued to over-60s and registered consumers: with it, you could walk into a pharmacy with your identification and buy up to 10 grams of the world’s finest dope.

“It was a unique practice before the Islamic Revolution,” explained Doctor Arash Alaei.

“Opium was given out based on strictly defined criteria, including the age of the addict, rather than just to anyone who wanted it. This made it possible to control the flow of drugs, protect young people from them, and help drug addicts from the poor part of the population.”

There were still some flaws in the coupon system: medication was often diverted to the black market, while many women, afraid of the stigma, never registered.

In 1978, millions of Iranians began marching through the streets demanding the Shah’s abdication. They rallied around Ayatollah Khomeini, who believed that Western culture is sick, decadent and needed uprooting. The Shah and his family fled the country the following year as protests spiralled out of control. Khomeini stood before cheering crowds and declared an Islamic Republic in 1979, ushering in an era of revolutionary terror far more violent than what happened under the Shah.

Even though they’d been present for thousands of years, drugs were framed as one of the foreign ills plaguing Iranian society; the coupon program was soon scrapped. Instead, those considered “addicts” were routed into public squares to have their heads shaved, while traffickers were hanged in their thousands. Shah sympathisers and regime opponents were accused of drug trafficking, legitimising their executions in the public’s eye. Alcohol, of course, also had to go.

Treating the post-Shah heroin boom

But drug trafficking showed no sign of slowing down. The Soviet invasion of neighbouring Afghanistan from 1979 onwards caused a boom in Afghan poppy farming, while Iran itself was repelling an invasion from Saddam Hussein’s Iraq (at the time backed by the US), leaving a generation of wounded and traumatised veterans searching for something to soothe their pain. Supply, meet demand.

While opium is usually smoked, heroin is injected; the global HIV epidemic soon reached Iran via syringe-sharing.

“Some of my classmates were injecting drugs. Some died, and this was a huge incentive for my brother and me to take action,” said Doctor Arash, who in the 1990s, along with his brother Kamiar, set up a free clinic in the western Kurdish city of Kermanshah for heroin users and others suffering from HIV.

“We had to find a common language with everyone we approached. In Iran, Islamic leaders have power over society. When we talked to them, we looked for different words than those we used to convince our patients or, for example, the police. When these local leaders learned of our results, they supported us in the Kermanshah health committee.”

Prohibition’s deadly return

Despite the reputation of a conservative theocracy, Iranian clerics could be surprisingly open-minded, allowing quite a bit of leeway in the framework of Islamic law. Harm reduction was accepted when framed in understandable ways: it is permissible to do something slightly evil if it stops a greater evil. Kamiar and Arash opened their clinics across the country and were internationally recognised as “best practice.”

But the government of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a hardliner who came to power in 2005, did not like this: acknowledging the HIV epidemic meant admitting that devout Muslims were injecting drugs and having sex. The shame! The Alaei brothers were soon accused of espionage.

“In 2008, step-by-step, they closed everything,” Arash remembered.

“They followed my car and arrested me at a gas station. The next day, they arrested my brother. At the trial, they asked me: do you have contacts at foreign universities? I said yes. They said it was evidence, and I could not deny it.”

The brothers were held in Evin Prison, home to many political detainees.

“We were supposed to have a half-hour walk in the prison yard every day. I came up with an exercise program to keep the prisoners physically active during the walk. The guards didn’t like it and they talked one of the prisoners into starting a fight with me. But mostly, we were calm.”

After international pressure, Kamiar was released early in late 2010, followed by Arash several months later. They now live and work abroad, while their clinics continue operating in Iran.

From calm to killings

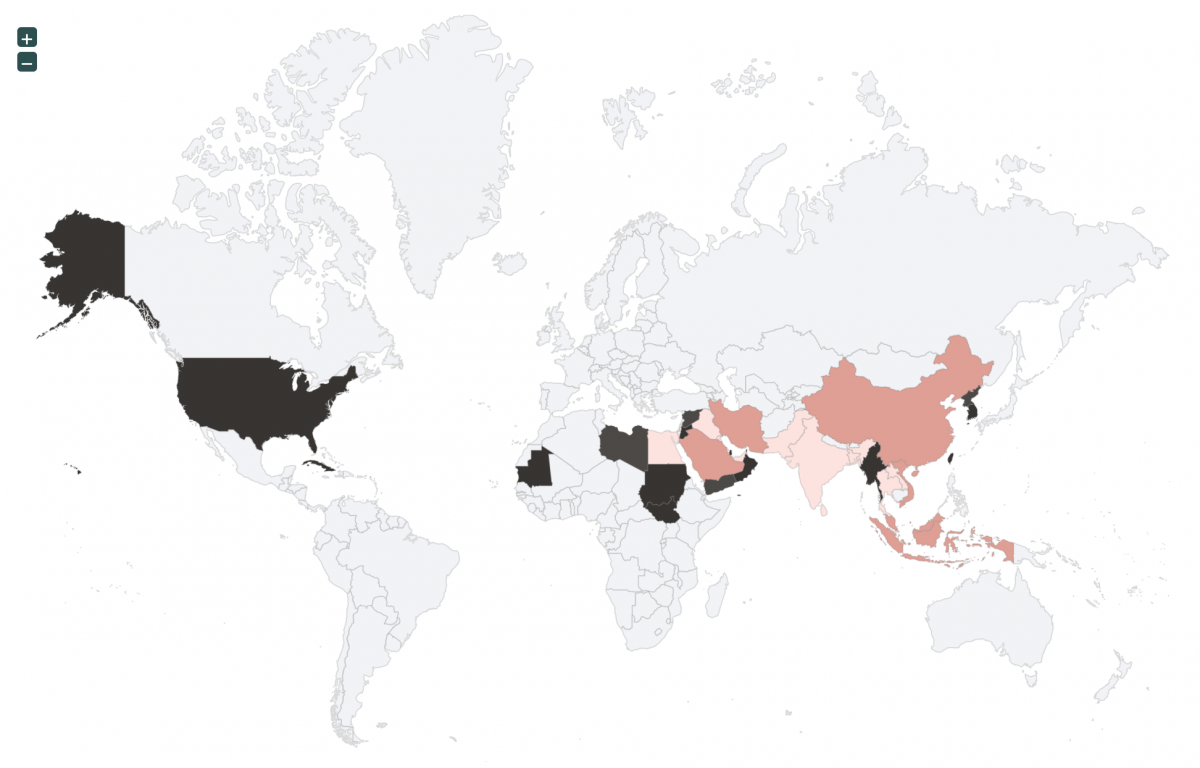

2018-2020 was a period of “calm”, with no more than 20-30 drug-related executions happening per year. However, since 2022, executions are back with a vengeance after popular protests for women’s rights and against rising living costs. At least 972 executions happened last year according to Amnesty, with more than half being for non-violent drug offences.

Alcohol’s maintained prohibition has also been deadly. The lack of access to legitimate sources means created a profitable industry for bootleggers who refilled discarded liquor bottles with industrial methanol, selling them as imported brands – with fatal consequences. In 2023, there were 2,103 deaths from alcohol poisoning.

Nothing lasts forever, and change will come in Iran – but it must come from within. For if there’s one thing Iranians – a proud, millennia-old culture predating most European civilisation – hate more than being told what to do by bearded old men, is being told what to do by outsiders.