There is a lot of hype around cannabis, landraces, and terroir. Yet, this hype about landraces and terroirs doesn’t mean that these terms are understood by most. In fact, it is often (yet wrongly) thought that cannabis landraces are “wild” cannabis populations, and that the terroirs are limited to the impact of soil and climate. Oddly, very little of the information around cannabis terroirs and landraces refers to their existing academic literature. As a result, the meaning of both has been blurred, or applied inconsistently, and led to many futile debates. The ensuing confusion has meant that the acknowledgment and recognition of the value of landraces and terroirs is more difficult, and actually impedes the protection of cannabis’ global agrobiodiversity.

So, what is a terroir, what is a landrace, and how do they relate to each other? Read on for more details.

Terroir

Terroir, a 13th century-old French word, is a term used to refer to a defined agricultural area. A terroir can yield products (named ‘terroir products’) that, in turn, have a specific typicity that is unique. ‘Typicity’ is a term borrowed from the wine world used to describe how a product reflects the various origins and characteristics of its terroir: for example, how much a Merlot demonstrates the expected flavour profile of a Merlot.

What makes an agricultural product a ‘terroir product’ is its typicity and its originality. This includes the typicity and originality of the aroma and flavour, but also the uniqueness of its psychoactive effects, which is particularly important for cannabis.

A terroir is both a physical location, but also a historical environment, a collection of all the inherited knowledge of production adapted to local biophysical and human conditions. Because of this, a terroir is determined by both its natural and cultural environments: it is an expression of how non-genetic factors, such as environmental and cultural factors, can impact the hereditary information (i.e. genotype) of a plant as well as the local evolution of its morphology, its developmental processes, and, most importantly, its biochemical and physical properties.

Landraces

Landraces have a lot in common with terroirs, for a landrace is a domesticated variety of a plant (or animal) species that, due to geographical isolation and human selection, is an expression of its unique natural and cultural environment. Both terroirs and landraces are therefore geographically and historically determined.

Terroirs are reservoirs of diversity

Very much like a landrace, a terroir does not develop on its own or naturally; it is ‘constructed’ by its natural factors (such as soil composition and climate), but also human and cultural factors, developed as a result of its historical production in a specific location by a specific human community. These communities bring in their own technical knowledge, developed over time through an evolving process of accumulation of individual and collective experiences.

This makes terroirs the product of a collective cultural heritage: the cultural knowledge of a given society or social group, often that of a local peasant population. In that sense, a terroir results from a system of interactions between environmental factors (soil, climate, topography, hydrography, flora, fauna, micro-organisms, etc.) and human factors (economic, social, political, and cultural characteristics, crop cultivation and livestock production systems, production practices and techniques, skills, etc.). It is easy to understand, therefore, that one cannot create a terroir, no more than a landrace; they are not created, but rather, inherited from history and the surrounding ecosystem.

Terroirs matter because they are reservoirs of diversity, setting a typicity, originality and reputation that cannot simply be exported or replicated elsewhere. Terroir products are in some ways the opposite of standardised products: they are by definition characterised by an inherent diversity within their typicity.

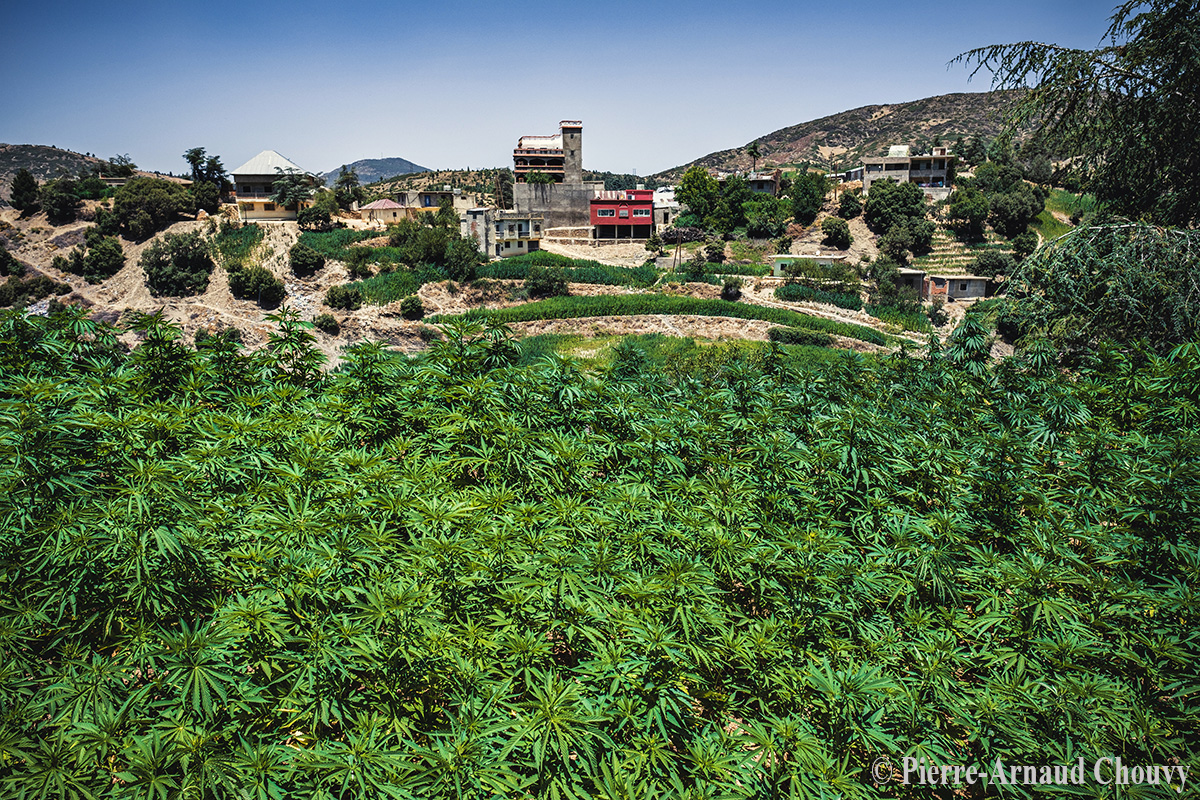

Moroccan kif hashish, a terroir product

There are in fact singular terroirs that exist in the world, where their products are created from such a unique intersection of an indigenous landrace and its surrounding physical and human factors. These archetypal terroirs (or arch-terroirs, as I like to call them) are ecological systems that are at the mercy of aggressive cultivating and environmental changes. The recognition and protection of arch-terroirs is essential to the conservation of cannabis’ biodiversity.

This is the case with Moroccan hashish. Recent changes in its production are an example of how the typicity (or the typical flavour and aroma) of a terroir product can change according to the variety of cannabis cultivated in the same area. The introduction of modern cannabis hybrids in the mid-2000s in Morocco has led the production of a very different hashish than that what had originally been produced from kif¸ the Moroccan landrace. This has resulted in the production of a hashish of Moroccan provenance (where it is produced), but no longer of Moroccan origin (where it is from).

While the distinctive Moroccan hashish made from the kif landrace can legitimately be considered a terroir product due to its typicity, its origin, and its production environment, the more potent and now-standardised Moroccan hashish produced from modern hybrids cannot. Interestingly, the latter hashish is disliked by local producers and consumers, and also by some international consumers alike. Consequently, traditional hashish, made from the kif landrace, can nowadays fetch a much higher price than that produced from modern hybrids.

Why this matters for modern cannabis

The concepts of terroir and landrace are now more relevant than ever for the cannabis industry, as cannabis legalisation and its “green rush” of fast development of large cannabis companies pose a threat to the genetic and cultural diversity of cannabis, as well as to the existence of small cannabis farmers worldwide.

In the end, acknowledging the existence of, and actively conserving cannabis terroirs and landraces, can only come to benefit as a form of conservation and promotion of biological, cultural, and sensorial (especially through varied flavours and aromas) diversity. This could be potentially done by developing an appellation system for cannabis, frequently used by the wine industry to protect geographic-specific production.

Protecting terroirs can further:

- Promote typicity in a consumer-led market that veers towards standardisation and commodification;

- Promote low-input and low-carbon farming systems, building on local knowledge and practices;

- Make ecologically coherent farming systems possible, transforming small farming into more financially viable ventures;

- Value and respect geohistorical specificities, traditions and heritages (landraces developed in isolated areas partly because of prohibition) without denying progress and economic development.

The future of cannabis terroirs and landraces can blossom into a successfully conserved future: some initiatives, such as the Californian Department of Food and Agriculture’s Cannabis Appellation Programme are looking to promote regional collaboration on cannabis production. Yet these initiatives need to spread globally, especially in the Global South where small cannabis farming and genetic diversity stand to suffer the most from foreign financial pressures and aggressive changes in production.

*Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy is a geographer and CNRS Research Fellow. He has written extensively about the value of terroir as a concept for cannabis production, as well as a focus on Moroccan hashish as a terroir product. His work can be followed on Geopium and on Instagram.