Belarusian organisations Legalize Belarus and Youth Bloc, which advocate for humane drug policy and respect for human rights, published a study (in Russian) analysing their country’s drug policy, outlining recommendations for the Government to create alternatives to incarceration and improve conditions for people using drugs.

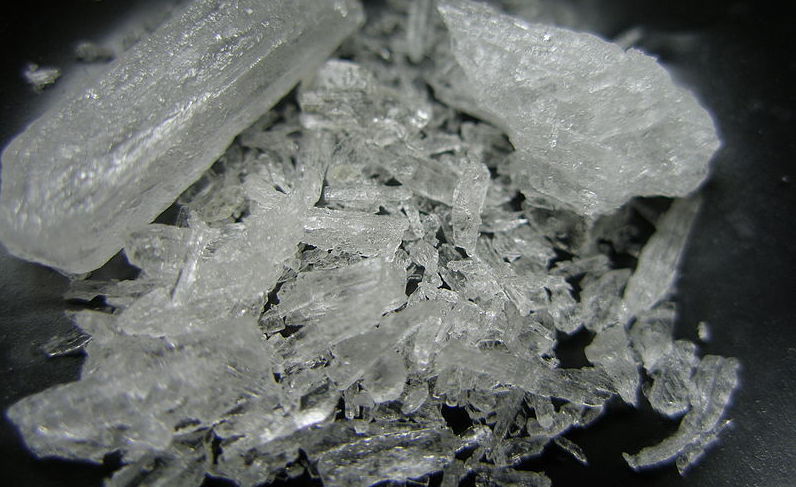

From 2015-2020 in Belarus, 17,217 people were convicted for drugs-related criminal offences. However, most of them were guilty of use or possession, never having the purpose of selling them. This underscores the repressive nature of drug policy in the country, and the disproportionately high percentage of those serving sentences in penal colonies for crimes related to psychoactive substances.

According to Belarusian law, mere possession of any quantity of psychoactive substances is punishable by up to 5 years’ imprisonment. Distribution of prohibited psychoactive substances is punishable by imprisonment of up to 15 years. For the same actions committed by an organised “criminal” group, one can receive up to 20 years of imprisonment. For actions resulting in death as a result of substance use – up to 25 years in prison.

What we do know is that stigmatisation and marginalisation of substance users can lead to increased dependence or even death.

During detention and initial interrogation of a detainee, in most cases, the right to defence is a luxury, not a right. Defendants are often detained before their trials, kept in cages during court hearings; there is no presumed innocence. Many of those convicted are subjected to torture and beatings by law enforcement officials in order to obtain confessions or other information, a practice common across repressive regimes.

Fuelled by a reward system and performance targets, officers from the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA) are known to detain people using drugs regularly, who have not committed violent crimes or caused harm to anyone. This is evidenced by the statistics of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Belarus, which shows that more than 50% of sentences were given for possession with no intent to sell. Thus, up to ten thousand people between 2015 – 2023 were imprisoned only for having decided to use psychoactive substances. In Belarus, as in other countries, simply sharing drugs with friends means you are a distributor in the eyes of the law.

Importantly, such punitive repression against people using drugs and small-scale distributors has virtually no effect on the market for psychoactive substances, and does not reduce demand. What we do know is that stigmatisation and marginalisation of substance users can lead to increased dependence or even death. In our country, there is a widespread practice of persecution of Opioid Substitution Therapy (OST) patients, HIV-positive people and other representatives of vulnerable groups who are associated with substance use. These individuals are subjected to discrimination, control and pressure from the MIA, and can often have employment opportunities taken away. In addition, OST patients are sometimes forced to take the blame for petty theft and other crimes under the threat of withholding their access to medication.

Also, repressive drug policy prevents the ranking of substances in the legislation according to their degree of possible harm, restricting the chance to study these substances and use them for medical purposes. For example, in Belarus, the legal consequences for possession of cannabis and alpha-PVP, psilocybin and heroin are exactly the same. People receive large prison sentences even for substances that are legal for recreational use in many other countries.

Another problem with our current approach to drug policy is the lack of preparation for new psychoactive substances that have unpredictable effects on the human body. The effects of these substances are not well understood and can have serious consequences. For example, a striking case is the situation in the early 2010s in Belarus, when there was a so-called “spice epidemic”. These were new synthetic cannabinoids that entered the market, seeking to mimic cannabis’ effects. They quickly flooded the market due to a low price, ease of manufacturing and, most importantly, their legality. This led to tragic health consequences for many users.

While some countries have been able to explore the use of psychoactive substances to assist in treatment for mental health conditions, Belarus has no legal structure to explore these treatments. Their continued criminalisation prevents their study and use in medical practice. The only recent example of introducing a new method of treatment in the country was the opening of the OST programme for methadone delivery in December 2022. However, access to the programme is dependent on a mandatory registration within the clinic, which many patients refuse to do for fear of state surveillance and future legal issues, meaning uptake has been limited.

It should also be noted that it remains a challenge for opioid users to access naloxone. In 2021-2022, Belarus experienced an increase in the number of overdoses of street methadone imported from Russia. These fatalities could have been prevented with an established mechanism regulating over-the-counter dispensing of naloxone, but the Ministry of Health believed that its access would increase the number of people using opioids.

Legalize Belarus and the Youth Bloc call on the Belarusian authorities to introduce the following legislative changes:

- Authorise the controlled distribution of psychoactive substances for medicine and scientific research;

- Decriminalise the possession of small amounts of psychoactive substances for personal use;

- Distinguish responsibility in the sphere of illicit trafficking of psychoactive substances depending on their quantity and type;

- Introduce educational programmes in the field of psychoactive substances;

- Provide comprehensive harm reduction services

The study is available here in Russian.