Part 1: The Case Against Decriminalisation

As a new attempt to control drug-related harms in a non-punitive fashion, the Oregon decriminalisation model has had an unsteady start, struggling with an incredibly toxic drug supply and a short implementation period. This has not been helped by what intense targeting of opinion pieces, perspectives and columns across all major American news outlets, criticising the model’s implementation.

As a reminder, the Oregonian system decriminalised the possession of all drugs in November 2020. Drug possession is now only punishable with a $100 fine, which is removed if a person attends a health screening through a recovery hotline. This system also diverts money previously used for law enforcement into drug prevention and treatment centres (which the police were not happy about), as well as using recreational cannabis tax revenue to fund treatment and addiction services.

Contextually, Oregon is also surprisingly average in its overdose rates. Oregon ranks 33rd in the US for drug overdoses (out of 50 states), just above the average. The states ranking above it all have more prohibitive and punitive models of drug control than what Oregon is attempting. The amount of attention that such an average state is receiving feels quite bizarre and warrants investigation.

While there is a need to critique new drug control systems and ensure they are working properly, the amount of critical attention that Oregon has received has been exceptionally high. Over a dozen articles from the New York Times, the Washington Post, The Economist and the Globe and Mail have attacked Oregon’s model, either due to failing to reduce drug-related deaths, or by highlighting how other decriminalisation systems – namely Portugal – are struggling, and that Oregon will somehow have the same fate. Thematically, these articles have some similarities, superficially engaging with Oregon’s decriminalisation system while failing to recognise the structural faults that led to the North American epidemic of drug dependence and overdose in the first place.

In this piece, I examine what are the most salient critiques of decriminalisation found in all the pieces analysed (full list at the end of the article), and what are the proposed solutions.

“Shattered glass and human feaces”: the spectacle of public drug use

The stark visibility of drug use is often repeated as an example of the failures of progressive drug policies. Bret Stephens, Opinion Columnist for the New York Times, lays out several anecdotes of people using drugs outdoors in Portland, Oregon’s largest city. A bar manager described seeing people passed out on the streets, public sex and tent encampments. In another NYT article, a photo report from July 2023, the same bar manager is quoted; this time saying she’s aware there are longstanding societal problems driving drug-related despair, but that drugs are its primary driver. A similar story is repeated by the Globe and Mail in June 2023 in the Canadian province of British Columbia (BC), where people are spotted using drugs outdoors.

Visible drug use is often presented as a reminder of the chaotic and dangerous nature of drug use. People using drugs are somehow desecrating public spaces and the communities they inhabit with their “anti-social” habits. This is a tactic older than the War on Drugs: drug researcher Susan Boyd highlighted that since the mid-1800s images are used in media of drug users and traffickers as “dangerous classes”, often a racialised “Other”, building an idea of a threatening and infiltrating group of outsiders that endanger social stability. Even in 18th Century England, sensationalist images of drunk working-class people were used to depict the supposed degradation alcohol caused to society. And while alcohol continues to be a drug with elevated levels of drug-related harms, we have found ways to minimise these harms, while raising funds for awareness and treatment. Through decriminalisation and regulation.

The NYT photo report interviews a drug user that describes Portland as a “homeless drug addict’s slice of paradise”; the Washington Post quotes a Portuguese citizen describing people using drugs as invading their city; these are common descriptions of alien, un-desired people infiltrating a society.

In the more modern War on Drugs, dangerous outsiders are “routinely caricatured” in the worst and most vile scenarios possible, which are extensively used in the sources we examined: from people having sex in public, finding excrements on the street, inconvenient tents, people wearing ski masks, drug use near schools and playgrounds. Insidiously, it feels like these snapshots of drug use are used to exaggerate drug use to such an extent that cracking down on them is the only possible – even “noble” – thing to do for the good of society.

The focus on drug material littering streets is frustrating, given how harm reduction interventions often focus on addressing these exact issues. Discarded material in public places is often indication of a lack of safe drug-using spaces and other progressive measures than of an inherent lawlessness defining people who use drugs. From drug-specific bins in drug using areas, needle and syringe programmes, or safer injection sites to ensure drug use is done in a maintained space, there’s a whole array of options that address the visible and chaotic nature of public drug use and connected littering. These measures are often encouraged and funded by systems of decriminalisation.

The sensationalism of all things related to drugs perpetuates their demonisation. Only one letter from a NYT reader mentioned that people struggling often endure other issues like homelessness and mental health conditions, which make it difficult to respond to their drug-related problems. When the focus lies on the public nature of drug use, the heart of the issue – such as the lack of housing, access to treatment and/or safe drug-using spaces – remains unaddressed. These depictions of drug use continue to encourage the exclusion of people using drugs, which is what led to the explosion in drug-related social ills in the first place.

Individual failings over systemic issues

Across most of the articles, systemic issues that have led to mass homeless encampments and a toxic drug supply are mostly ignored, preferring instead to blame individuals for their choices. Public drug use is framed as selfish behaviour, rather than an indication of a housing crisis; street overdoses are perceived are taken as gluttonous drug consumption, rather than a poisoned drug supply. As the NYT puts it, “addicts are… people who often will do just about anything to get high, however irrational, self-destructive, or…criminal their behaviour becomes.”

It should not come as a surprise that overdoses are more frequent in more economically disadvantaged areas. In fact, poverty, unemployment and homelessness are known to be key drivers of higher drug-related risks. As Morgan Godvin highlighted in TruthOut, before Measure 110 was implemented in February 2021, Oregon was already seeing a massive homelessness spike: from 2020 to 2022, chronic homelessness (defined as being homeless for more than one year) rose by 56%.

While drugs may impact homelessness, the effect that rising living costs (particularly around housing) on the visibility of drug use cannot be denied. However, drug users are blamed for the structural issues that exacerbate problematic drug use in the first place. As Godvin further highlights, a housing crisis combined with a toxic drug supply means that “the suffering of our neighbours is not occurring behind closed doors, but rather right in front of our faces”. It is the widespread abandonment of people in precarious living and working conditions that is the driver of this, impacting many in society including those that already used drugs.

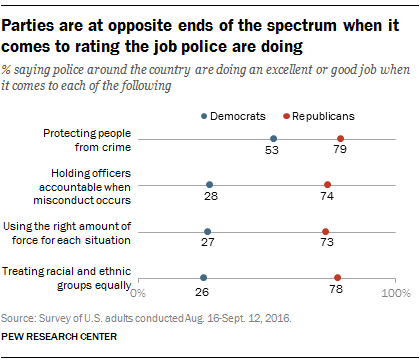

“Police blame drugs for crime”: The US culture war around cops

Attitudes towards the police, particularly in post-George Floyd America has deepened the growing partisan gap between conservative and progressive values and political beliefs. Harm reduction advocates increasingly recognise how policing is a key driver of drug-related harms: both from the racist enforcement of drug laws across the world, to the daily harassment that police commit against people who use drugs.

Meanwhile, conservatives largely consider policing to be the primary force which maintains a healthy and morally good society. As such, police are the authority best suited to assess current threats to society and combat them accordingly. While both sides may agree change is needed, they’re ultimately relying on narratives of very different groups to shape their understandings of drug problems, and what needs to be done.

Across all articles we examined, none spoke with healthcare professionals delivering harm reduction initiatives within Oregon.

Across the NYT and the Washington Post, police are portrayed as having their hands tied by decriminalisation: police in Oregon state that it’s better to ignore people using drugs than taking them in for treatment; Portuguese police blame a rise in crime in decriminalised Portugal on “increased drug use”, with no data to back this claim. In partly-decriminalised BC, the Washington Post claims there is no stigma towards drug use, citing a police chief that says no one has been arrested for “simple possession” since 2019 – while harassment of people using drugs continues.

The police continue to be the source relied upon for commenting on and informing drug policies. Across all articles we examined, none spoke with healthcare professionals delivering harm reduction initiatives within Oregon. The police however are consistently given an opportunity to comment, when by definition their role in decriminalised systems should be reduced. Even when discussing decriminalisation, which seeks to re-orient drug interventions from a criminal legal to a health-based perspective, the media continues to wrongly rely on police as a dominant authority on drug harms.

For many, police are still seen as a key agent in combatting crime and maintaining social order. Alec Karakatsanis, a civil rights lawyer and chronicler of police abuses of power, has repeatedly outlined that it is still widely believed that the War on Drugs is a “natural effort to reduce the perceived harms associated with drugs use”. It follows that the police deserve our sympathy and respect as well-intentioned actors seeking to address drug problems, rather than viewed as the catalyst of harm and punishment.

Media outlets are pushing, intentionally or not, the idea that the drug problem is just as bad under decriminalisation and prohibition, that individuals (not systems) are entirely responsible for their circumstances, and that the police are the ones trying to prevent more drug-related harm. This has several consequences.

First, it discredits the idea of decriminalisation as a viable drug control model for the US, even before it is given a proper chance and time to work. Decriminalisation is presented as something that works abroad, but “not for us”; it cherry-picks Portuguese evidence, to portray how even decriminalisation’s poster-child has come to regret it (totally ignoring the effects of decades of imposed austerity in the country).

Second, it firmly embeds drug policy reform into the ongoing American culture war: supporting decriminalisation and alternatives to punishment and incarceration for drug possession as a progressive vs conservative issue. It is the corrupt and morally weak individuals that must deal with their own problems, or be subjected to treatment; the structural faults that led to an explosion of drug-related issues are acknowledged in passing as a typical progressive whine.

The resulting effect is a culture of criticism, but no new attempts; despair with inaction, yet disdain for change. The culture war, fed by the pieces analysed here, prevents bipartisan support for drug policy change, as it is perceived through the wider political lens that is polarising American democracy.

The next piece will analyse the solutions proposed in the media, either by the authors themselves or by those platformed in the stories.

The articles examined for this piece were:

New York Times

-

The Perils of Legalization (24 April)

-

Scenes From a City That Only Hands Out Tickets for Using Fentanyl (31 July)

-

The Hard-Drug Decriminalization Disaster (1 August)

-

Is Portland’s Decriminalization of Drug Use the Right Approach? (13 August)

Washington Post

-

Wage war on fentanyl or decriminalize? We must find a way to combat it (27 December 2022)

-

Why decriminalizing drugs is a bad idea (10 April)

-

Canada decriminalizing drugs in British Columbia will prolong suffering (28 June)

-

Once hailed for decriminalizing drugs, Portugal is now having doubts (7 July)

Globe and Mail

-

Alberta lacks data about how many people need addiction treatment services (22 February)

-

C.’s drug decriminalization experiment is off to disastrous start (6 June)

-

Editorial: Unrelenting drug overdose deaths demand an unrelenting policy response from governments (4 July)

-

(Published in The Province, in Canada) Time for a third way on drug addiction policy in Canada (3 May)

Economist

-

Oregon botches the decriminalisation of drugs (13 April)