In Latin American media, the tragedy of the opioid crisis and fentanyl in the United States is understood through such headlines: “Lives Interrupted by Fentanyl: What Hurts the Most Is Waking Up and Needing a Dose.” “Fentanyl: Ecuador and Neighboring Countries on the Radar of Cartels of the Feared Drug.” “Fentanyl, the Other Epidemic Advancing From China and Cannot Be Eradicated.” And most recently: “The 5 Devastating Consequences of Fentanyl, the Drug That Caused Robert De Niro’s Grandson’s Death.”

The alarming facts about fentanyl are repeated over and over again: its potency 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine, its more accessible price and higher level of dependency that make it more profitable than other substances, and its staggering mortality rate that has already caused more deaths than the Vietnam and Iraq wars combined. Against this backdrop, United States Secretary of State Antony Blinken brought together representatives from 84 countries to tell them: “If we don’t act together with fierce urgency, more communities around the world will bear the catastrophic costs.”

The fear of fentanyl in Latin America is not unwarranted; however, the despite regional proximity, the region’s drug markets seem very different to North America. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), while there has been a significant global increase in the non-medical use of opioids and the number of overdose-related deaths, the crisis is not universal. “The crisis is actually multi-faceted in nature and its characteristics diverge sharply in different geographical regions,” explains the organization in a 2020 report.

The story of fentanyl in the United States is already well-known: the misconduct of pharmaceutical company Purdue Pharma, which concealed the high addiction risks of its medication OxyContin; the push for excessive prescription rates; the subsequent tightening on opioid prescribing when the evidence emerged, leaving people without access to a substance they had become dependent on; and the inevitable rise of a massive market for cheaper illegal synthetic opioids like fentanyl and other analogues.

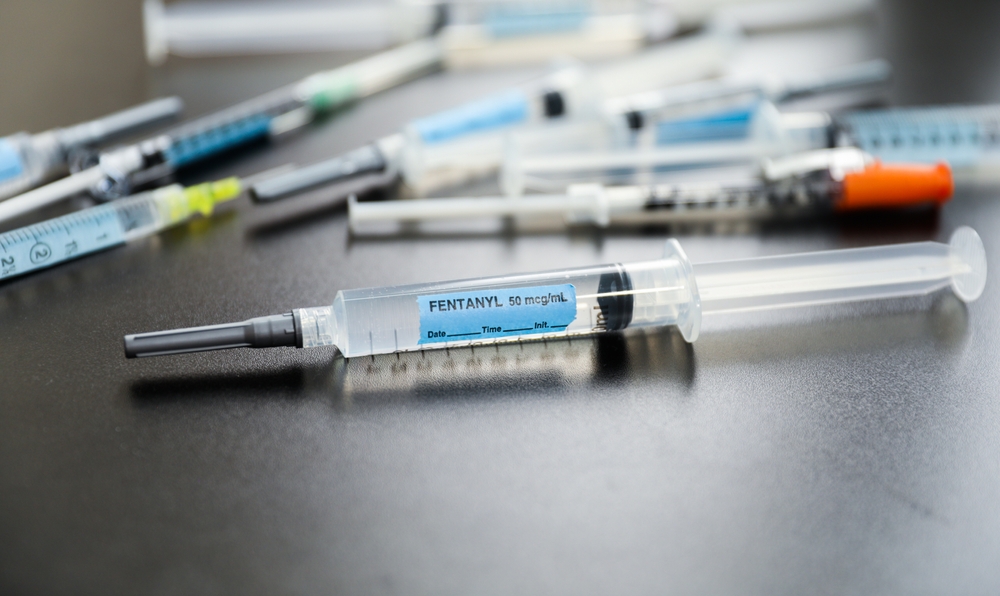

The nature of the opioid crisis in North America is largely driven by high rates of non-medical opioid consumption and the adulteration or substitution, to reduce costs, of illicit supplies of heroin and diverted pharmaceutical opioids with fentanyl, fentanyl analogues, and other synthetic opioids. Unlike legal fentanyl that comes in pills or ampoules with specific doses for medical use, illegal fentanyl is produced with no controls, clear dosage or strength, and sometimes found mixed in other substances. Due to its high potency, the slightest difference in the quantity used can mean the difference between life and death.

The reality in Latin America appears to be very different. The UNODC indicates that for the South American region, the annual prevalence of non-medical synthetic opioid consumption was around 0.2% in 2018, six times lower than the global estimate of 1.2%. While these figures are a few years old, it demonstrates that the prevalence of synthetic opioids in the Americas is lower than what it would be expected to be, particularly given the market’s proximities.

Mexico: A Border Pivot

(Official State Department photo by Chuck Kennedy)

In the northern region, in Mexican cities like Tijuana, Mexicali, and Ciudad Juárez, fentanyl is indeed a harsh reality. A study published in 2020 revealed that in northern Mexico, approximately 93% of the analysed samples of white powder heroin contained fentanyl.

As has been the case throughout its history, being the neighbouring country of the United States has represented a unique complexity for Mexico. The opioid and fentanyl crisis is no exception. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was an intercontinental shift in the movement of fentanyl when Wuhan’s port was closed, disrupting the traditional transit route for the drug. Since then, according to the DEA, Mexican cartels have become the main suppliers of fentanyl to the United States.

In Mexico, fentanyl was first detected in border town of Tijuana in 2018. The arrival of heroin mixed with fentanyl has created a difficult situation, explains Alfonso Chavez, coordinator of NGO PrevenCasa’s harm reduction programme. Increasingly they saw homeless people, who are marginalised from public institutions due to stigma and criminalisation, presenting with an increase in abscesses caused by injections, and cases of both fatal and non-fatal overdoses, adding to other risk factors such as HIV and Hepatitis C due to the use of unsterile syringes.

Furthermore, additional challenges have arisen, such as a shortage of methadone. The lack of substitution opioids meant many individuals using it for treatment had to return to heroin use, which was adulterated with fentanyl.

The figures and images of this tragic context fuel fears of fentanyl throughout the region, but the truth is that it does not represent the reality of Mexico or Latin America. Speaking in the recent International Forum on Fentanyl, organised by the Mexican Government, researcher Jaime Arredondo concluded that, contrary to the alarms often spread by the media, “fentanyl is not everywhere,” but is found especially in the illegal opioid supply, and is primarily a border phenomenon.

“Regarding fentanyl consumption in other parts of the country, not much is known,” explains Chavez. “We don’t know when these new drug cuts may reach other communities because local markets are very dynamic and always at the forefront.”

Colombia: More press than presence

There are three reasons why a similar scenario is unlikely to occur in the rest of Latin America, according to Julian Quintero, director of the Colombian harm reduction organization Échele Cabeza: the region does not have a historical dependence on opioids; fentanyl would not be profitable given the regional availability of cheap and high-quality heroin; and because Latin Americans prefer stimulants over depressants.

“The rumour is that fentanyl will appear in the tusi,” Quintero explained in a recent interview. (Tusi is a mixture of MDMA, ketamine, caffeine, and an increasingly diverse range of additives that originated in Colombia and has rapidly spread throughout the continent). “But it also happens that journalists buy into the story told by dealers who claim to use fentanyl in their recipes, but when you go and analyse it, it’s not true. Caution is necessary.”

In Colombia, the media has consistently fuelled fear about the presence of fentanyl. The attorney general even held a press conference to announce a fentanyl seizure, claiming it was “the drug causing 300 deaths in the United States every day.” It was mediatised fear-mongering: they were medical-grade fentanyl ampoules, routinely used in hospital settings.

As a result of all these rumours, Échele Cabeza conducted targeted drug analysis sessions to rule out the presence of fentanyl in their substances. The result? They found no fentanyl in samples, suggesting that it was either not in the market, or available in such low quantities it was undetectable. What did cause concern was the presence of benzodiazepines and oxycodone as adulterants in some psychoactive substances. But the presence of illegally manufactured fentanyl has not yet been detected.

“We also don’t see users being very concerned about fentanyl beyond asking,” explains Quintero. “And that may be because we haven’t seen a massive death toll in Colombia resulting from fentanyl. We don’t see here, like in the United States, six people dying in a park because the same dealer sold them fentanyl and they didn’t know how to dose it. In Colombia, that impact of mass deaths due to consumption has not been observed. We haven’t seen, for example, what happened in Argentina.”

Argentina: a scare, a warning

What happened in Argentina shocked all of Latin America and made global headlines. In February 2022, in the Puerta 8 neighbourhood of Buenos Aires, a series of people arrived at emergency rooms after consuming adulterated cocaine. 24 people died. It took authorities a week to identify the substance that had caused the disaster, and anxiety reigned in the region: was fentanyl here?

No. It was carfentanil, a synthetic opioid significantly more potent than fentanyl. Once the hysteria passed, it was never determined whether its use was an accident, or it had been deliberate, or whether it was a revenge ploy between micro-trafficking groups.

As in other Latin American countries, rumours say that fentanyl has been found as a cutting agent in ketamine or tusi doses. However, to this day, the drug checking program PAF!, run by the organisation Intercambios, has not detected fentanyl in Argentina.

“The fear of fentanyl is very present in the minds of users since the incident with adulterated cocaine, as well as due to the poor translation that the media does about the opioid epidemic in the United States and the spectre of fentanyl as a cutting agent everywhere,” says Carolina Ahumada, coordinator of PAF! and deputy director of the organisation Youth RISE. “Neither the police, who conduct the most sophisticated analyses, nor the Ministry of Security have issued an epidemiological alert regarding the presence of fentanyl as a cutting substance or its presence in psychoactive substances.”

For Ahumada, the preference for stimulant use and the tight regulation over prescribed opioids and their derivatives have kept fentanyl consumption at bay in Argentina. The lack of historical use of these drugs in this part of the world is also significant: “When we talk with other international organisations, they wonder why opioids are not common in Argentina and Latin America compared to other substances that are much more prevalent, such as cocaine and smoked cocaine,” she explains. “The answer is somewhat confusing because if cocaine reached the United States, why couldn’t fentanyl reach [Latin America] in such a globalised world?”

Minimum requirements

In any case, the work of the Mexican, Colombian, and Argentine organizations mentioned above reflects what multiple reports from international organisations support: substance analysis programs allow for the identification of the real composition of substances, enabling individuals to make informed decisions and generate early warnings. Widespread access to naloxone is crucial to reverse overdoses. Syringe exchange programs reduce the risks of viral diseases like HIV and hepatitis. Supervised consumption services provide a safe environment for drug users. Harm reduction programs improve people’s relationship with any substance.

Decades of prohibition have made it clear that the illegal drug market is uncontrollable and unpredictable. However, years of harm reduction strategies implemented by organisations worldwide have also established the minimum requirements that prevent catastrophes, with or without the presence of fentanyl.