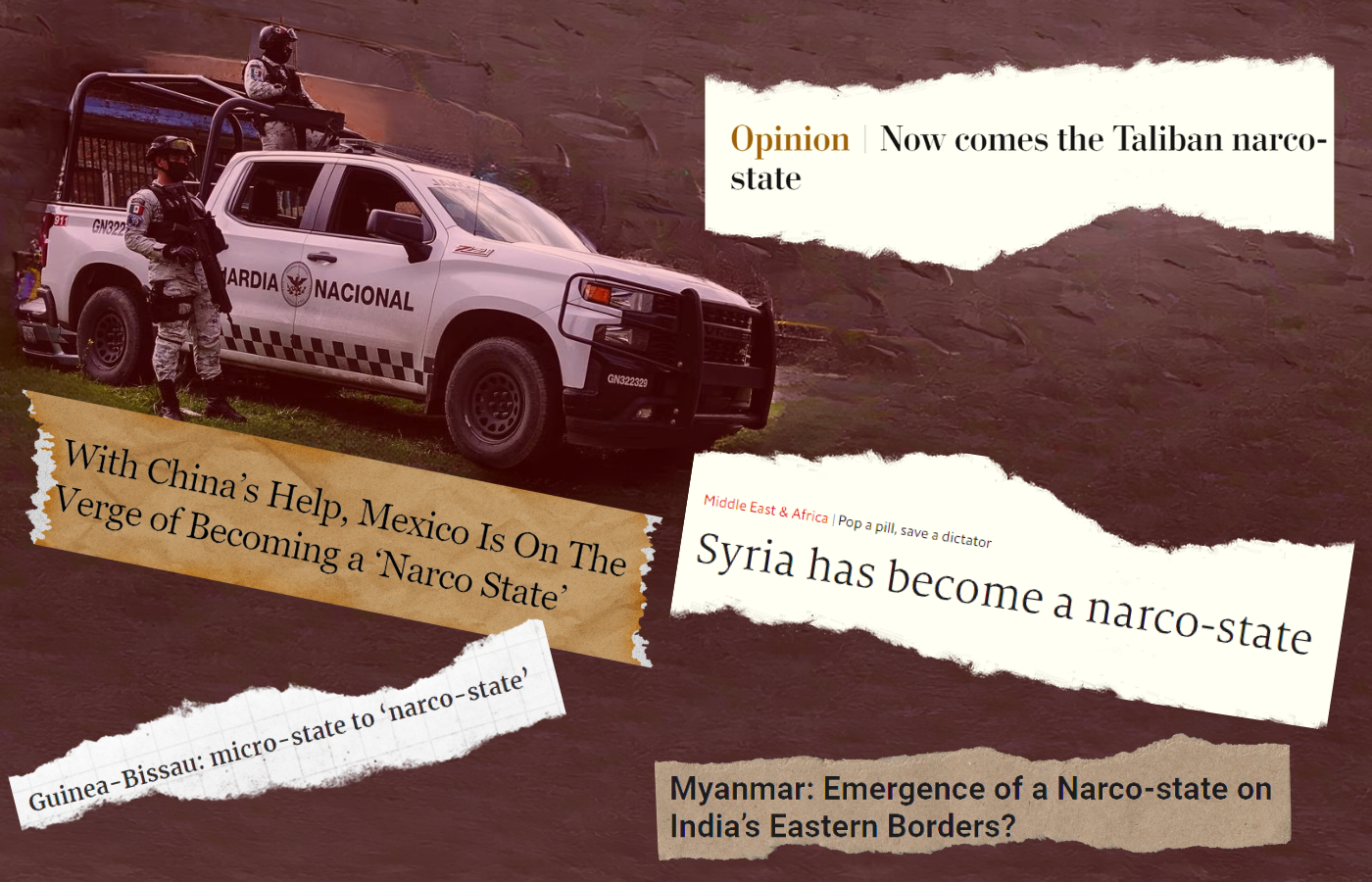

The term “narco-state” has been used by politicians, journalists, and law enforcement agencies since the 1980s. While it was initially used to describe Latin American nations like Colombia, Bolivia, Peru, and, a few years later, my home country of Mexico, the term has continuously been applied to more and more countries.

In 2008, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) referred to Guinea-Bissau as Africa’s first “narco-state”. This label has also been liberally applied, particularly by the media, to countries across Asia, like Afghanistan, Syria, Myanmar, among others. Definitions of a “narco-state” vary; some focus on the state’s economic reliance on the drug market, others define a certain level of institutional corruption, or comment on levels of insecurity. What is similar between all these countries is that drug trafficking is perceived as a source of political power and economic gain, leading to complex relationships between state actors and drug traffickers.

More recently, the chairman of the police board in the Netherlands has used this label to describe the country’s escalating drug-related violence, making it the first European country to be labelled as a narco-state. However, he was quick to qualify: “We aren’t Mexico”.

The Netherlands’ narco-state description has also been used to argue against the decriminalisation of drugs, blaming their non-punitive drug model for attracting the illegal drug trade. Again, the author draws a clear distinction:

“Unlike countries like Mexico or Colombia, the Netherlands is one of the richest and most developed economies in the world. It has a sound rule of law, low levels of corruption, and a very low murder rate.”

Blaming decriminalisation for the creation of the Dutch narco-state was argued by the Argentinian politician Patricia Bullrich, demonstrating the dangerous potential of how this label opens a field of prohibitionist attacks that undermines drug policy reform.

Discussions of a narco-state resurged in Mexico during the trial of the former Public Security Secretary, Genaro García Luna, who has been found guilty for facilitating bribes to protect organised criminal groups, and simulating the destruction of 23 tons of cocaine, only to return the original shipment to traffickers.

It’s easy to understand why there’s a need for a term for the historical, powerful, and violent collaboration between organised crime, high-profile politicians, and armed forces. However, it’s important to question the validity of this term, what sort of consequences its use encourages, and how it may be perpetuating the already significant stigma and discrimination against people in these countries, whether they’re involved in the drug trade or not.

The power of the narco-state label

Narco-state is applied so liberally across different contexts, that it has been criticised for overly simplifying complex situations. Not only does it fail to describe the relationship between drug cartels and the state accurately, it reduces countries and all of the actors involved in the drug trade to mere criminals, collectively making their country “ungovernable”. This perpetuates the idea that the population of a country cannot abide by “the rule of law”, a harmful stereotype often attributed to non-white people. As a member of the Latinx community, we are often faced with absurd questions, insensitive jokes about notorious criminals such as El Chapo or Escobar, or nonsensical Netflix-fuelled portrayals of our homelands simply because they are associated with “narcos”.

At the same time, we constantly see how the media glorify law enforcement agencies who portray themselves as the heroes of the war on drugs. The social stigma can result in unfair treatment that impacts our daily lives and that, in a way, perpetuates drugs as a taboo or interchangeable term with organised crime, preventing open conversations about drug use, harm reduction, or alternatives to prohibition.

The narco-state label can also limit foreign investments only to those going into security measures, such as the militarisation of police forces and anti-narcotics efforts, which are known to fuel societal violence in the name of cutting drug supply at the source. This is particularly ironic given the amount of wealth and financial stability that money from drug-related activities generates for banks: there’s ample evidence that billions of drug trafficking money from “narco-states” is often laundered in Swiss, British, Italian and American financial institutions. Somehow this doesn’t make them narco-states.

The term lacks complexity, and according to Professor Patrick Chabal, the concept of a narco-state is too neat, clear-cut, static, and predictable. It implies a clear and fixed line between the good and bad guys, often the state and organised crime. So while the term “narco-state” is an appealing catch-all term perfect for headlines or easy narratives, its indifferent use often hides a complex underlying reality.

What about other similar terms?

“Failed state” is often synonymously applied, with Mexico having the distinct privilege of being a combined “failed narco-state”. But this is just as pejorative of a term, encouraging in today’s hyper-globalised society whatever foreign military or bureaucratic interventions needed to turn it into a “successful state”.

While state fragility may refer to a nation’s ability to guarantee peace and democratic governance, failed states imply a loss of a government’s monopoly on violence, justifying military and political interventions to restore the state’s power. The West, often the US, has used the term “failed state” strategically since the 1990s (and especially after 9/11), particularly to define places that require devastatingly violent interventions by foreign powers to restore supposed “order”. A “failed state” is perhaps more indicative of a country’s foreign policy objectives than the actual ability to govern and maintain relative peace. It is also a term that I have not (yet) seen be used to refer to a Western nation.

Narco-states is a useless term, mostly used to overly simplify the complex relation between organised crime, states, global markets, and populational involvement in the drug trade. What it does do, is drive stigma for country perceptions, as well as encourage violent interventions, often by national or foreign weaponised agents. It’s crucial to consider the impact of our words, embrace a language and understanding that acknowledges the complexity of reality on the ground, and that Latinx is not synonymous with narco.

And while it is important to ensure democratic processes of governance and stability within nations and regions, this catch-all term does little to promote a human-rights, non-stigmatised understanding of the world. It’s important to remember that drug prohibition fuels drug-trafficking violence and that “narco-state” and “failed state” labels simultaneously encourage war-like interventions and prevent dialogue on non-violent alternatives.